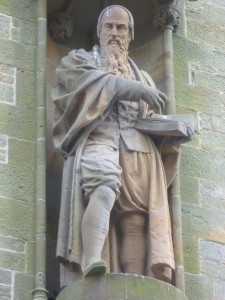

John Knox: Misogynist or Ladies’ Man?

by Marie Macpherson

2014 marks the 500th anniversary of the birth of John Knox, yet surprisingly little has been written about the founding father of the Scottish Reformation. Writers veer away from him, no doubt because, in the popular imagination at least, Knox has become a caricature of himself: the cartoon Calvinist who banned Christmas, the pulpit-thumping misogynist who wrote the notorious polemic, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. Whatever else he may have achieved, Knox’s notorious ‘blast’ has reverberated throughout history, drowning out the legacy of ‘the one Scotchman to whom all others, his country and the world, owed a debt’ – in the words of the historian Thomas Carlyle.

2014 marks the 500th anniversary of the birth of John Knox, yet surprisingly little has been written about the founding father of the Scottish Reformation. Writers veer away from him, no doubt because, in the popular imagination at least, Knox has become a caricature of himself: the cartoon Calvinist who banned Christmas, the pulpit-thumping misogynist who wrote the notorious polemic, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. Whatever else he may have achieved, Knox’s notorious ‘blast’ has reverberated throughout history, drowning out the legacy of ‘the one Scotchman to whom all others, his country and the world, owed a debt’ – in the words of the historian Thomas Carlyle.

So who was John Knox? While Knox wrote reams about his later life, he was notoriously tight-lipped about his first thirty years. Several facts have been established, however. He was born in Giffordgate, on the banks of the River Tyne in Haddington, East Lothian around 1513/14. His father was killed at Flodden and his mother died soon after, leaving Knox and his brother William orphans. He attended the local grammar school before going on to St Andrews University, but for some reason did not graduate. Then, in 1536, though he was ordained a Roman Catholic priest, he served as a notary apostolic at St Mary’s Collegiate Church in Haddington.

Around 1542 he became tutor to the sons of local Protestant lairds, but it was the charismatic reformist preacher, George Wishart, who changed the course of his life. According to Knox, he was born again when Wishart pulled him from ‘the puddle of papistry’. Dropping everything to follow him, Knox took up a two-handed sword to serve as his bodyguard. Finally arrested by Cardinal Beaton’s henchmen, Wishart ordered Knox to flee so as to escape the punishment for heresy that he endured in St Andrews in 1546 – burning at the stake. Two months later Fife lairds murdered Beaton and hung his body from St Andrews Castle before salting it like a side of beef in a vat in the dungeon.

A year later, Knox came out of hiding to serve as chaplain to the Castilians under siege in St Andrews. When the French broke the siege Knox was arrested and sentenced to toil as a galley slave. Meanwhile, the Treaty of Haddington that betrothed the young Queen of Scots to the French Dauphin was signed in 1548. By a stroke of coincidence, Knox may even have been rowing the galley that ferried the young queen to France.

After his release 19 months later Knox was outlawed in Scotland. Instead, the English reformers sent him as preacher to the north of England. Hearing of his rousing sermons, Edward VI called him to London to serve as a royal chaplain. On the death of the Protestant king, the accession of Catholic Mary Tudor incensed Knox. He fled to Geneva to wrench a statement from Calvin that the reign of a female Catholic monarch was unnatural or, as he called it, ‘monstrous’. Calvin baulked at the fiery Scotsman’s fervour and sent him off round the continent to consult other leading reformers. None supported him.

In his wilderness years as an exile in Geneva, Knox preached daily, debated hotly with English reformers and married his wife Marjory Bowes, who bore him two children. He also made heroic journeys, traipsing back and forth from Geneva to Dieppe in response to Scottish lairds begging him to return to Scotland but then changing their minds. With the ‘monstrous’ reign of Mary Tudor still rankling, he wrote his infamous First Blast, which so outraged Calvin that he banned it from Geneva. Badly aimed, Knox’s revolutionary diatribe was also badly timed because, months later, Mary Tudor died and the Protestant Queen Elizabeth ascended the English throne. Not at all amused by this seditious pamphlet, she banned both publication and author. Knox had no option but to return to Scotland where the Protestant Reformation was underway. The final part of his life is better known and recorded, including his tempestuous relationship with Mary, Queen of Scots. Ironically, it was not Knox, deposer of monarchs, who beheaded the anointed queen, but her Protestant female cousin.

So why did I write about such a controversial character? The dour, finger-wagging bogeyman is hardly the obvious choice for the hero of a novel, but I was researching the Treaty of Haddington when I stumbled across Knox the galley slave. How did he end up there? That piqued my curiosity to find out more about the man behind the myth.

Knox’s silence about his early life raised many questions. How did a poor orphan lad receive a university education only available to the sons of the nobility? Who funded his education? Why did he not graduate? When and why did he turn away from the Church of Rome? As I raked over the scrapheap left behind by biographers and historians, I unearthed fragments that had been overlooked, enough bare bones to construct a story, but one that could only be told as fiction.

In most biographies of Knox, the poet and playwright Sir David Lindsay is barely mentioned. But the man who not only coaxed Knox out of hiding but inspired him to sound his first blast against the Catholic Church at St Andrews must have had a greater influence on Knox than he was given credit for. The radical ideas expressed in his play, Ane Satire of the Three Estates, a scathing attack on the Catholic Church, must have affected the young priest. Indeed, the role of Divine Correction could have been scripted for Knox – perhaps it was. The striking similarity between one of Lindsay’s poems and Knox’s first sermon suggested that the playwright may not only have written it, but also directed the young preacher-in-waiting.

Knox also had kinship with the Hepburns of Hailes. His forefathers had served under the Hepburn banner, and Knox acknowledged James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, as his liege lord. Had the Hepburn family taken responsibility for the poor orphan? If so, John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews, who had endowed the college where Knox was educated, was the most likely benefactor. To protect family interests the prior had ensured that his niece, Elisabeth, was appointed prioress of the wealthy St Mary’s Abbey where the Treaty of Haddington was signed. But this spirited prioress refused to bend the knee, for she is reported in historical documents as riding to the hunt with James V’s court and then, more controversially, being accused of ‘carnal dalliance’ in 1541. As notary apostolic, did Knox have to clear up the scandal? Amongst the cast of corrupt clergy in Lindsay’s Satire, the prioress is exposed as a scarlet woman who excuses her behaviour by blaming those who compelled her ‘to be a nun and would not let her marry’. Did the real-life Prioress Elisabeth Hepburn inspire the role?

Around 1546, jealous of his influence on her young son, James V, Queen Margaret Tudor exiled Lindsay to Garleton Castle outside Haddington. Did he meet Elisabeth? At this time Knox was attending Haddington grammar school and serving as an altar boy at St Mary’s Church. Did all three become acquainted and, if so, in what way?

All these coincidences involving this trio were just too tempting to ignore and so, blending these few tantalising scraps of historical fact with inspired guesswork, spiced with a liberal dose of artistic license, I cooked up a story with a dark secret at its centre. Like Knox’s original work to which the title refers, The First Blast of the Trumpet makes some startling claims and controversial conjectures.

But any discussion of John Knox must address the issue of his notorious tract, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, for which he has been severely lambasted as a rampant misogynist. But was he? With its highly charged and usually misinterpreted title, this controversial document appears to launch an attack on the whole of womankind as a battalion of battle-axes.

Knox’s aim, however, was to challenge the right of female monarchs to inherit the throne on the premise that it was against nature for a member of the weaker sex to rule. But it was not his assertion of women as inferior beings that was shocking – most of his contemporaries, male and female, would have agreed, for women were treated as minors in law. No, what alarmed them was Knox’s call to depose and, if necessary, execute an ungodly monarch. That was tantamount to treason.

Yet, in spite of his controversial ‘blast’, Knox did not hate women. On the contrary, the ‘bearded one’ loved women and, perhaps even more surprising – they loved him. Like many charismatic preachers, Knox attracted a retinue of female followers, but he genuinely seemed to enjoy the company of women – at least those who agreed with his religious ideas. Not only was he married twice, but other men’s wives left their husbands to follow him. In his correspondence with his mother-in-law, Elizabeth Bowes, Knox the firebrand comes across as patient and understanding, tender and caring and not at all condescending. To me, this affinity with women implied a strong female influence in his life. In the first book of the trilogy, I suggest that this was his godmother, Prioress Elisabeth Hepburn.

While The First Blast sounds the fanfare for his 500th birthday, Book Two of the trilogy follows Knox in exile, where his life reads more like an adventure thriller than a history. Against the backdrop of public events – revolution, religious strife, political intrigue – his turbulent private life is played out like a soap opera, with dollops of sexual jealousy, adultery, ménage à trois, birth, and death. In contrast to the usual portrait of Knox as a bible-basher, The Second Blast of the Trumpet aims to pull him down from the pulpit to show the reformer’s more human face as lover, husband, father and friend.

About the contributor: You can read more about Marie Macpherson and how she combines an academic’s love of research with a passion for storytelling at http://mariemacpherson.wordpress.com/about. The Knox Trilogy is published by Knox Robinson Publishing (http://www.knoxrobinsonpublishing.com).

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 68, May 2014