History & Film: My Cousin Rachel

Bethany Latham

Olivia de Havilland and Richard Burton in My Cousin Rachel.

My Cousin Rachel: The Beauty of Ambiguity

In my personal canon of Gothic literature, Daphne du Maurier is one of the greater saints. By the time I discovered her, she had long since aged out of bestseller status, known to most only through Hitchcock’s adaptations of her work (e.g., Rebecca, The Birds). From my first encounter, I wanted to devour everything she had written, novel and short story. That first pre-teen encounter happened to be My Cousin Rachel (Victor Gollancz UK, 1951 / Doubleday US, 1952).

My Cousin Rachel is unique in that it takes one of the primary tenets of Gothicism and flips it: Gothic novels usually feature a young, naïve heroine – her youth and inexperience put her at a decided disadvantage when dealing with the older, romantic hero/anti-hero. It is this worldly male who has all the secrets, serving an almost pedagogical function for the poor young woman as she makes her way through the formulas inherent in Gothic plotting. Du Maurier chose to make her protagonist male, and the inversion offers some interesting corollaries.

In the early Victorian era, Philip Ashley is an orphan, raised by his older cousin, Ambrose, on an estate in Cornwall. Ambrose is the very best of replacement parents. Adamantly opposed to the interference of females, his household is all-male, even the dogs – a contented, testosterone-tinged world. So it comes as a surprise when Ambrose, who has traveled to Florence, begins sending missives home to Philip about the widowed Contessa Rachel Sangalletti, a distant cousin. It’s an outright shock when he writes soon after that he has married her. Things immediately take a dark turn; Ambrose’s health fails. He writes he is constantly watched by his wife and her “friend” and lawyer, Rainaldi. Perhaps he is being poisoned. He begs Philip to come to him at once. “She has done for me at last, Rachel, my torment.” Philip sets off posthaste, but arrives too late: Ambrose is dead. Doctors diagnosed a brain tumor that caused Ambrose to lose his mind, prey to all kinds of terrible suspicions. The villa is unoccupied, and no one knows where Rachel has gone, including her “friend” Rainaldi, whom the grief-stricken Philip instantly distrusts and dislikes.

Philip is all vengeful passion, a reaction that would have been highly problematic in a female narrator. He wants nothing more than to visit suffering on those who, he believes, are responsible for his beloved cousin’s death. When Rachel almost immediately shows up in Cornwall, he gets his chance. Yet when he meets his cousin, she is not at all what he had expected, and from the outset Philip doesn’t stand a snowball’s chance. Rachel is attractive, sophisticated, charming; she brightens up the house, encourages Philip to smoke in her boudoir and catch glimpses of her hair down, her nightdress. Soon his vengeful passion is just passion, and Philip is pouring the family jewels in his cousin’s lap. He cannot wait (literally, he’s ready to go at the stroke of midnight) for his 25th birthday when he comes into his majority and the estate…so he can also hand that over to Rachel.

Philip’s friends, his legal guardian Nicholas Kendall and Kendall’s daughter, Louise, are plagued with anxiety. Though Rachel charms all she meets (even the dogs flock to her), there are rumors of financial profligacy and a first husband dead from dueling with one of the contessa’s lovers. She is also a decade Philip’s senior. Still, no one can speak sense to the rash young man, whose obsession trumps all sage advice and his own mistrust. When Rachel grants him a carnal return on his estate investment, he is the happiest of men. In a fashion almost universally reserved in such stories for unworldly girls, he incorrectly equates sex with love and an acquiescence to marry. Thus, his shock is immeasurable when he announces his betrothal to a gathering of birthday guests, and Rachel promptly assures everyone he’s either drunk or over-tired, and to think nothing of his outburst. A clause that the estate will revert to Philip if Rachel remarries ensures she has no intention of re-entering the matrimonial state. The only way she could and keep what she has gained…is if Philip were dead. Rachel is skilled in herbs and makes healthful teas (“tisanas”); Philip falls ill. (You see where this is going.)

A simple enough and somewhat familiar plot, except perhaps for the gender reversal. Even Rachel’s name, Sangalletti, puts one in mind of blood. Yet du Maurier has accomplished a masterwork of ambiguity here. Her writing style is propulsive, and there are enough disparities and contradictions to call all assumptions about Rachel into question. Philip, as narrator, cannot put conflicting pieces together with certainty. What type of woman is Rachel, truly? Is she guilty of murdering Ambrose? Of attempting to murder Philip? Du Maurier herself, when asked, simply said she did not know, for she had put herself in Philip’s place as the teller of the tale, and he must reconcile all the contradictory elements at play. The narrator finds himself unable to pronounce innocence or guilt. So it is up to the reader to decide. For me to say more would entail spoiler alerts, so I advise simply reading the book. Or…watching a film adaptation. (This is History & Film, after all.)

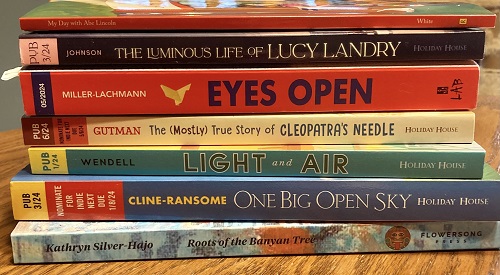

Though it is Philip telling the story, Rachel is the character who most fascinates; she commands Philip’s attention and ours. In Hollywood’s Golden Age, a year after the book was published, the rights had already been auctioned and actresses were queuing up to play her (Greta Garbo, Vivien Leigh, et al.) in 1952’s adaptation. The role went to Olivia de Havilland, with Richard Burton as Philip, in his first American film role. As is his wont, Burton chews the scenery with relish – he is suitably vengeful, passionate, and obsessed. He’s not called upon to be much more, and the jury is still out as to whether he ever manages to elicit sympathy. His anger and willful blindness leads him into needless cruelty to those who care for him most, such as Louise (Audrey Dalton). De Havilland, by contrast, is the very picture of subtlety, and an absolute delight to watch. The second she steps onscreen, all eyes are on her. She is uniformly charming, composed, and knows all the right moves to make, especially with men. There are times when her delivery seems angelic and others when it is tinged with the sinister. When Philip, uncomprehending, finds a different “morning after” than he expected, she offers an indulgent smile and coolly rebuffs him with, “That was last night. And you had given me the jewels.” De Havilland’s Rachel is an unapologetic liar; when Philip confronts her about secret visits to Rainaldi, she is entirely nonplussed. Her greatest gift as an actress in this film is maintaining the ambiguity, with every look, every gesture, every line delivery. As one critic observed, “Once the titular widow makes her entrance, there is nary a moment throughout the remainder of the picture when the viewer can conclusively state that de Havilland’s role is that of a master manipulator, or just a beautiful, sophisticated yet ultimately unfortunate woman who is a problem magnet.”1 By the end of the film, I was struck with a desire to immediately re-watch it, to observe Rachel more carefully – every word she says and action she takes, as well as what others say of her. To seek further elucidation. Despite an impressive performance by de Havilland, it was Burton who was nominated for an Oscar, for Best Supporting Actor.

Naturally, I was somewhat intrigued when I saw, floating around the Internet, that a new adaptation of the novel was in the works, which eventually turned into last year’s My Cousin Rachel, starring Rachel Weisz in the titular role and Sam Claflin (of Hunger Games fame) as the callow youth. Much has changed in the realm of women’s roles since the 1950s, and I was interested to see how this would manifest itself in this new adaptation. Filmmakers can seldom resist modernizing historical characters to cram them into a promotional mold for their current agendas, sometimes in hilariously ridiculous fashion (I refer you, digressively, to Netflix’s travesty, Anne with an E, for a prime example). Writer and director Roger Mitchell didn’t disappoint on that score; he has stated that he wanted “Rachel to feel in part like a woman from 2017 who parachuted into that world.”2 Perhaps her crinoline helped slow the descent? So now we have a Rachel who furiously exclaims, “Can’t you let me be a person in my own right?!” when Philip offers to support his penniless cousin with a generous allowance. She would prefer to teach Italian, to work. Philip, shirtless for some reason, blusters, “I simply will not permit it!” For all her expository proto-feminism, Weisz’s Rachel is a great deal more weepy woman than de Havilland’s. The waterworks occur with great frequency and to immediate effect on Philip, who has “never seen a woman cry.” Claflin mostly mixes painfully inexperienced with soulful and occasionally unhinged (there are multiple instances of throat throttling). Philip is also intentionally obtuse. He cares not for “books or cities or clever talk.” One loses count of how many times other characters explain something to him with various versions of “Do you understand?”

Weisz’s Rachel shows herself to be somewhat of a chameleon: she is witty yet suitably decorous with Philip’s English friends, down-to-earth with those who work his land, and almost wholly foreign when she lapses into rushing Italian (complete with over-animated hand motions) with Rainaldi. The impression is that it is this last shade which is closest to the “real” Rachel. This adaptation raises more than once the specter of the half-Italian Rachel as a sort of foreign menace. Ambrose preemptively defends her from unvoiced criticism in his first letters: “She is as English as you or I.” Before he meets her, in his rage, Philip thinks to see “hysterics, isn’t that what one expects of Italians? All that macaroni – she’ll probably be too fat to get up the stairs.” One of the very traits that makes Rachel appealingly exotic marks her as not fully English, and therefore, to Philip and his coterie, at once lesser and dangerous. She is described as a woman of “very strong impulse and passion” as well as “unbridled extravagance and limitless appetites.”

In comparison with its 1952 counterpart, the 2017 film does have various strengths. The supporting actors (Iain Glen as Nicholas Kendall and Holliday Grainger as Louise, in particular) exhibit far more depth and acumen than than their 1950s predecessors. The film is also worth watching for the cinematography alone: gorgeous shots of the Cornish coast, immersive interiors, and sunlit, color-saturated exteriors. One scene in particular, a wince-inducing outdoor romantic encounter, is stunning in its use of the vibrant pop of color created by bluebells against verdant wood and field. The 1952 adaptation, as a black and white film shot almost entirely on a sound stage, cannot compete in this arena. Its sets are dark and unsettling, deep shadows lit by candlelight. It often evinces an almost noir-like feel that adds to the oppressive tension (and the appeal for this lover of noir).

While Weisz is not wholly disappointing in her portrayal of such a complex character, she lacks de Havilland’s subtlety and, most especially, the driving force of the novel and its previous film adaptation: ambiguity. It is not entirely Weisz’s fault. Mitchell has appreciably tipped the scale, attempting to imply Rachel’s innocence in a variety of ways. Rainaldi is removed as a romantic rival (read: threat) – Mitchell has made him gay. Rachel is not a blatant liar; she simply omits things that might be “upsetting” to Philip, as she explains to him. Certain other aspects of the original plotting are left out or changed, and with each slight modification, the balance tips further in Rachel’s favor as the film attempts to sway viewers – thereby depriving us of one of the main joys of this tale. The novel and the 1952 film adaptation began with the line, “They used to hang men at Four Turnings in the old days. Not anymore, though.” This is a nod to the penalty for murder, and at the same time, a reflection that now those accused must be given a fair hearing. The verdict cannot be a foregone conclusion. Rachel must have her hearing, and it is the reader/viewer who should sit as jury. The 2017 version opens with the musing, “Did she? Didn’t she? Who’s to blame?” and then does its best to answer that question for us. Unfortunately.

References:

1. Edgar Chaput. “Friday Noir: My Cousin Rachel.” 3 February 2017. CutPrintFilm website (http://cutprintfilm.com/features/friday-noir-cousin-rachel). Accessed 15 July 2018.

2. Laura Varnam. “New Adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel Will Leave You Wondering Long After Credits Roll.” The Conversation website (https://theconversation.com/new-adaptation-of-daphne-du-mauriers-my-cousin-rachel-will-leave-you-wondering-long-after-credits-roll-78546). Accessed 10 July2018.

About the contributor: Bethany Latham is the Managing Editor of Historical Novels Review. She has authored various nonfiction books, numerous journal and magazine articles, and is a regular reviewer for HNR and Booklist.