Historically Speaking: A Retrospective on Georgette Heyer

by Jennifer Kloester

Jennifer Kloester explores the novels of best-selling author Georgette Heyer

Jennifer Kloester explores the novels of best-selling author Georgette Heyer

In February 1920 a teenage girl accompanied her family to Hastings for a holiday. Her younger brother was convalescing, and the small seaside town was dull. To relieve their boredom the young woman devised a serial story. It was an eighteenth-century tale, full of passion and romance, featuring a disgraced earl turned highwayman, a cynical, saturnine duke and a beautiful heroine. It proved an enthralling saga, and the girl’s father encouraged her to write it out and send it to a publisher. Eighteen months later, in September 1921, Constable published The Black Moth by Georgette Heyer. She was just nineteen.

More than ninety years later, more than thirty million copies of her books have been sold; The Black Moth is still selling and (despite her death in 1974) Georgette Heyer remains a perennial bestseller, loved around the world for her historical novels. During her fifty-three year career Heyer wrote across different genres and time periods, writing short stories, contemporary and detective fiction and historical fiction set in the medieval, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is these latter two eras which were her particular forte, and it is with the English Regency period of 1811-1820 that her name has become synonymous.

Of the fifty-five novels published during her lifetime, fifty-one are still in print. Of these, twenty-six are set specifically within the Regency, when George III was mad and his son ruled as Regent in his stead. Like her enduringly popular eighteenth-century novels – These Old Shades, Devil’s Cub, The Talisman Ring and Faro’s Daughter – Heyer’s Regencies are compelling stories abounding in comic irony with memorable characters whose lives and situations are ordered by the historical realities of their time and class. She loved mining primary sources for ‘recondite details’ or ‘the sudden bit of erudition that every now and then staggers the informed reader’, and she had a remarkable ability to distil effortlessly a wealth of historical detail into her stories. Today, her period dialogue has become a byword among historical novel readers and writers.

While Heyer could never divest herself of the perceptions or influence of her own era and her twentieth-century sensibilities inevitably permeate her novels, she was a master at creating a sense of the past. Her novels come to life with their depictions of upper-class Regency life, its fashion, modes and manners, with the historical details woven so deftly into the text that sometimes it is difficult to separate the historical from the fictional.

Heyer’s ability to ‘re-create the past’ is due, in large measure, to her immersion in the primary sources. Although she read widely among secondary sources, she preferred material from the period; Fanny Burney, Thomas Creevey, Charles Greville, Sarah Lennox, Captain Gronow and Elizabeth Wynne were among her preferred writers. She had a vast reference library which included original sources such as Blackmantle’s English Spy; The Hermit in London; Harriette Wilson’s memoirs, all of Wellington’s Dispatches and Egan’s Life in London. Contemporary magazines, guidebooks, sporting and domestic tomes were vital resources and Heyer was meticulous in her description of Regency fashion, furniture, carriages, hunting, fencing, fist-fighting, gambling and domestic management.

Heyer had no formal training in history. Until she was thirteen she was educated at home where her father, George, encouraged her love of reading and writing. He was a writer himself and father and daughter often read and edited each other’s work. It was only when her father went to war in 1915 that Heyer finally went to school. There she outshone her peers and found her intellectual equals among the teaching staff. She did not go to the university. Instead, she read the Greek classics, Shakespeare, Renaissance and Victorian poetry, her favourite, Jane Austen, Dickens, and the nineteenth-century historical novelists.

Heyer’s approach to history was influenced by the great literary historians: Edward Gibbon, Thomas Macaulay, James Froude and Thomas Carlyle, who were still widely read and admired in her youth. From them she learned the importance of original sources. From historical novelists such as Walter Scott, Bulwer-Lytton, Mrs Gaskell, Alexandre Dumas (père), Charlotte Yonge and Thackeray she learned to invoke a vivid sense of a period, its key players and events. Although she never thought of her novels as serious history, Heyer took the history that she wove into them very seriously indeed.

In 1935, she wrote Regency Buck, her nineteenth book and the first set in the Regency. To prepare she read a wide range of contemporary sources and thoroughly acquainted herself with the people, fashions and social customs. Georgette rarely talked about her abilities, but Regency Buck prompted her to acknowledge her gift for creating convincing period dialogue: ‘Kindly note Purple Patch (Clarence’s proposal). Carola Lenanton [Oman] paid me the biggest compliment I’ve ever had by asking me whether I’d found it in some unknown memoir, & “lifted” it for my book. She said (though I shouldn’t repeat it) that “not one word was false, or out of place.”’

The purple patch was the Duke of Clarence’s assurance – after the heroine refuses his marriage proposal (he needed her money) – that his family would not oppose the match. Georgette had written a speech for the future king, William IV, that reveals her skill in distilling the weight of historical fact into light comedic dialogue:

“Oh you mean my brother, the Regent! I do not know why he should oppose it. He is not at all a bad fellow, I assure you, whatever you may have heard to the contrary. There’s Charlotte to succeed him, and my brother York before me. You may depend upon it he thinks the Succession safe enough without taking me into account. But you do not say anything! You are silent! Ah, I see what it is, you are thinking of Mrs Jordan! I should not have mentioned her, but there! you are a sensible girl; you don’t care for a little blunt speaking. That is quite at an end: you need have no qualms. If there has been unsteadiness in the past that is over and done with. You must know that when the King was in his senses we poor devils were in a hard case – not that I mean anything disrespectful to my father, you understand – but so it was. We have all suffered – Prinny, and Kent, and Suss, and poor Amelia! There’s no saying but that we might all of us have turned out as steady as you please if we might have married where we chose. But you will see that it will all be changed now. Here am I, for one, anxious to be settled, and comfortable. You need not consider Mrs Jordan.”

Heyer’s next two books extended and consolidated her Regency knowledge. In 1937 she published what would be her proudest achievement, her ‘Waterloo book’: An Infamous Army. In 1939 she wrote The Spanish Bride about Sir Harry Smith and the Peninsular Campaign. In each her scholarly rigour is obvious and, treading in her research footsteps, one can only be impressed by the breadth of her reading and her grasp of the innumerable details essential to such vivid re-tellings of these military campaigns.

The descriptions of the battles are especially convincing. In the second half of An Infamous Army – when the action is centred on Waterloo – Heyer stays close to the contemporary sources, imbuing them with colour and emotion until the past is practically brought to life again. Her ability to combine history with story was her greatest skill and even in the less serious historical novels it remains the hallmark of her work; the achievement lies partly in her ability to turn passive fact into lively and engaging prose.

It has been reported anecdotally that An Infamous Army was recommended to students at Sandhurst. Both Sir John Keegan and Major-General Jeremy Rougier have corroborated this claim. Major-General Rougier’s response is instructive:

I can illustrate the international respect that her book attracted. In 1964 I was a military assistant to a member of the Army Board (the top management of the Army) and he was paying an official visit to Belgium. We had a free afternoon; what should we do? “Why not ask the Professor of Military Studies at the Belgium Military Academy to give us a conducted tour of Waterloo?” I said, and so he did. It was fascinating; he knew the position of every regiment at any time on both sides. “At about 3pm Napoleon was standing here – no, here” he would say, moving 10 foot to record the precise spot. At the end I presented him with a copy of Georgette’s book and explained our connection. He was as near speechlessness as a professor of military history can be. “This” he said, holding up the book, “is the nearest to reality that one will ever come without having been there.”

Heyer’s research for these three books formed the foundation for all her later Regencies. There were many aspects of the era over which she skimmed – or ignored completely – such as the Radical movement, the factory system or political reform, but she felt no need to include every aspect of Regency life in her novels. As a historical novelist, she used the past to create her stories, delving deep for detail but not for the broader historical meaning; seeking to portray the period, but not to explain it explicitly to her readers.

Much of her Regency history is implicit in her books – especially in her later books such as The Unknown Ajax, Venetia, A Civil Contract and Frederica. Here, she ‘wears her learning lightly’, creating characters whose lives are both enabled and constrained by the realities of the period. By immersing herself in its broader social history as well as in its lively and engaging minutiae, Heyer was able to create characters who not only ‘lived’ within the Regency but whose (albeit fictional) lives were also shaped by its customs, manners and mores.

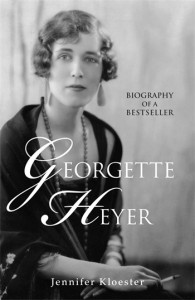

About the contributor: Jennifer Kloester has long been a fan of historical fiction and Georgette Heyer’s witty Regency novels in particular. After multiple trips to England researching Heyer’s life and writing, Jennifer was delighted to produce a new biography (William Heinemann, 2011) of the much-loved British author. Learn more at http://www.jenniferkloester.com.

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 62, November 2012