Historical Slang – Print Resources for Novelists: Part One

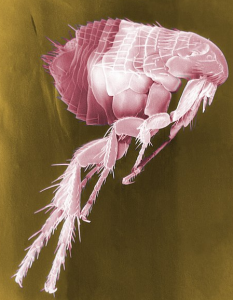

“Live stock” was slang for fleas and lice in the 1780s

Getting slang right for your time period and location is important for novelists. For historical slang, I found much more information in print books rather than online. The result is an old-fashioned bibliography/print book list, which will give you a place to start, though it can’t be comprehensive in this space.

I found so many books on this topic, I’m splitting this exploration into two articles. This first part includes general books on slang, and slang of particular populations.

The second part covers the military, politics and other areas: Military Slang, and Slang of Specific Fields.

If these books below aren’t available in your local library, many libraries will acquire them for their patrons via interlibrary loan service. I got all of these through the OhioLink academic library consortium that my workplace belongs to. If you don’t have a personal connection to a university, many academic libraries, in the U.S. at least, will interlibrary loan to public libraries. Failing that, you can try Amazon or abebooks.com to purchase secondhand copies. A few are available as free e-books: see entries below.

GENERAL GUIDES TO HISTORICAL SLANG

A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant, by Albert Barrere and Charles G. Leland. George Bell, 1897. (2 volumes)

Originally published privately in 1889, this would be useful for late Victorian-era slang. The title page says the work includes English, American, Anglo-Indian, pidgin, and gypsies’ jargon. Individual listings will include the realm of origin, such as: “billycock (Australian)=a kind of hat,” or, “ginger-snap (American)=a hot-tempered person.”

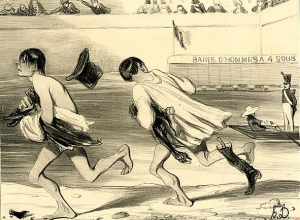

These gentlemen are “piking” (running away) in 1780s slang

A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, by Francis Grose, ed. Eric Partridge. Scholartis Press, 1931.

Originally published in 1785, this would be a good guide for an author writing a novel set in the 1700s. This edition has been edited by noted lexicographer Partridge, whose preface says he reproduced Grose’s original except for modernizing the usage of I/J and U/V. “Brandy-faced=red-faced,” “dimber=pretty,” “to pike=to run away.” An 1811 edition without commentaries is available at Project Gutenberg.

Macmillan Dictionary of Historical Slang, by Eric Partridge. Macmillan, 1973.

This is an abridgement of the author’s Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, “containing only those words and expressions which were already in use before the First World War, and which may therefore be considered as historical, rather than modern, slang”—Note On This Edition. Entries give dates, if known, such as: “flat-cap=a citizen of London…late C.16-early 18,” or “live stock=fleas; lice…from ca1780.” Partridge’s various works on slang are cited in other books listed in this article as a major source, so he’s considered an authority.

Clank: slang for a silver tankard in 1699

First English Dictionary of Slang 1699. Bodleian Library, 2010.

This is a reprint of A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew, by “B.E.,” considered the first English dictionary of slang and cant, “the secret language of the rogues, beggars and vagabonds who peopled the underworld of early England”—introduction. So if your novel is set around 1700, this would be a valuable resource: “clank=a silver tankard,” or, “peculiar=a mistress.”

The Oxford Dictionary of Slang, by John Ayto. Oxford University Press, 1998.

While this volume includes modern slang also, it’s valuable for historical novelists because every entry is dated, recording the earliest written record of the term, though the preface reminds users that most terms were used in spoken language well before they appeared in print. If a term is peculiar to America, Australia, or one of the former British colonies, that is also noted. The entries are not in straight alphabetical order, they are grouped under categories like crime, children, and religion. If you don’t know which category to consult, there’s an alphabetical index.

A Dictionary of Catch Phrases, American and British, from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Day, by Eric Partridge. Revised and updated edition, Stein and Day, 1986.

This is another work by noted slang scholar Partridge. Though a catch phrase is not the same thing as slang, it’s similarly informal language. I’m including it in this list, because historical novelists will want to avoid using a catch phrase that wasn’t from their book’s time period. Entries explain what the phrase means, and most entries include dates when the expression was first used. “My arse is dragging=I can hardly walk c.1915”, or, “With bells on=and how!, since 1909.” It seems to cover American, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand expressions as well as British.

HISTORICAL SLANG OF SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

A New Dictionary of Americanisms, by Sylva Clapin. Louis Weiss, [no date.]

The copy I examined had no publication date, but judging by its appearance, this book is likely from about 1900. The preface states that the volume also covers Canadian as well as U.S. expressions. “Duds=wearing apparel of any kind,” “Goose-egg=zero,” “shin-dig=ball or dance.” As of this writing, a 1902 ed. is available at Open Library.

The Oxford Dictionary of Rhyming Slang, by John Ayto. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Modern rhyming slang has its roots in history, and this volume includes both modern and historical. It includes dates when available for when a particular term first became known. It’s not in dictionary format; instead terms are grouped by topics, such as sex, gambling, illness, etc. If you wanted to have your 1850s character use “jack tar” to mean bar, this book will tell you that it’s a 20th century expression, not 19th; “there you are” was more common in the 1800s.

An eating house was called a “slap-bang” in mid-19th century New York

Vocabulum: or, the Rogue’s Lexicon, by George W. Matsell. George Matsell, 1859.

This volume, written by a policeman, is a dictionary to thieves’ cant in New York City in the mid-1800s. “Gilt-dubber=hotel thief,” “punk=a bad woman,” and “slap-bang=eating house.” An appendix has separate lists of gamblers’, brokers’, and pugilists’ slang. The copy I examined was printed on cheap paper, which has become very brittle. Libraries may refuse to lend, saying it’s too fragile to loan. Luckily it’s also available from Project Gutenberg.

The City in Slang: New York Life and Popular Speech, by Irving Lewis Allen. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Another New York-centered source, this book is in essay, not dictionary, format. For example, the chapter “Tall buildings” talks about the effect the city’s physical environment has had on language and slang expressions, along with doses of social history. Other chapters discuss sports, the underworld of the poor and homeless, and the city snob vs. the visitor from the country. This would be great to browse for story ideas, but to look up a particular “Noo Yawk” term, you’ll have to use the index.

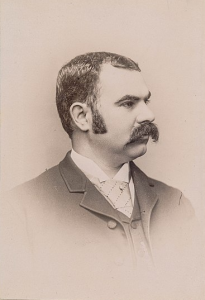

In 1930s America, this gentleman would be described as wearing a “lip muff” (moustache)

A Dictionary of American Slang, by Maurice H. Weseen. George Harrap, [no date.]

The copy I examined had no date on the title page, but the preface is dated 1934, so this should be valid for the first half of the 20th century. This is another guide to slang that is not arranged in straight dictionary format; expressions are grouped by chapters, such as Loggers’, Baseball, Money, and Eating Slang, etc. An index and an alphabetical list of subjects will help you find entries like, “Lip muff=mustache,” or, “Todlet=a small child.”

New Zealand Slang: a Dictionary of Colloquialisms, by Sidney J. Baker. Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd., [no date].

The preface is dated 1940, so I would assume this would be current for mid-20th century NZ slang. It’s not arranged alphabetically. Instead, you would consult a chapter such as “Gold” to learn about slang that arose during the gold rush in the mid-1800s, or “Twentieth Century” for more modern terms. One chapter covers the merger of Maori and English to form “pidgin” terms.

A Dictionary of Australian Colloquialisms, by G.A. Wilkes. Sydney University Press, 1985.

This book “seeks to record the history of each word, through examples of usage.” Citations and dates are given as examples of usage, really pertinent for historical novelists wanting to be sure a slang or colloquial Australian expression was actually in use in a certain period. “Rubbity=a pub,” from 1898.

Convict Words: Language in Early Colonial Australia, by Amanda Laugesen. Oxford University Press, 2002.

“A systematic study of the meanings of words used in the convict era”—back cover. Each word is defined, an etymology is given, date of the first recorded use, plus historical information to explain the context. “Government stroke=a deliberately slow pace of working,” or, “swell mob=a group of professional criminals.”

Black Slang: a Dictionary of Afro-American Talk, by Clarence Major. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971.

“This so-called private vocabulary of [B]lack people serves the users as a powerful medium of self-defense against a world demanding participation while at the same time laying a booby-trap network of rejection and exploitation.—introduction, p.9. This would be a good source for mid-20th century African-American slang. Some entries name the decade of popularity: “Conk (1940s): pomade for the hair,” “Ofay: white man (foe in Pig Latin.)”

Flappers 2 Rappers: American Youth Slang, by Tom Dalzell. Dover, 2010.

This is a reprint of the original 1996 edition with a new chapter for the Y2K generation. Chapters are arranged by decade, such as “The 1940s: the Jive Generation,” and “Hippie Counterculture of the 1960s.” Besides the dictionary listings, Dalzell inserts additional material, such as half a page of terms popular with slot-car racers in the ’60s, or greetings popular with the Hip-Hop generation. An index lets you look up a term if you aren’t sure which decade it came from. This would be a good story idea generator to dip into. Has anyone set a historical novel in the slot-car racing world before?

Dewdroppers, Waldos, and Slackers: a Decade-by-Decade Guide to the Vanishing Vocabulary of the Twentieth Century, by Rosemarie Ostler. Oxford, 2003.

Vocabulary of Americans, that is. This book is not in dictionary format, but is arranged by decade. This would be an excellent resource for someone setting a novel in, say 1900-1910, to browse the relevant chapter for ideas to include in their story: your characters might attend the “nickelodeon” (early movie theater that costs 5 cents/nickel to get in), attend a vaudeville “dumb act” (one with no talking or singing such as a juggler or dog act), or attend a rally of the “Wobblies” (Industrial Workers of the World labor movement.)

Western Lore and Language: a Dictionary for Enthusiasts of the American West, by Thomas L. Clark. University of Utah Press, 1996.

You might think from the title that the slang it contains is limited to Old West cowboy talk, but its scope is wider: “all the words and phrases included in this work originated in the West or are associated mainly with the West,” including California, Alaska, and the western Canadian provinces, and including modern terms. As an Easterner I had never encountered “borrow pit,” meaning a roadside ditch or pond, till my sister moved out West and I visited there; the term is included in this book. Naturally, many words originating in Spanish or Native American languages are included, such as “qantaq=traditional wooden bowl” [in Alaska]. If your novel is set in the North American West in historical or modern times, you will want to consult this work.

Happy Trails: a Dictionary of Western Expressions, by Robert Hendrickson. Facts on File, 1994.

This guide to Western slang and regionalisms is like the previous entry, it contains both historical and modern Western expressions. Some of the entries have dates, but you might want to cross-check words with the OED or another guide to be sure the term fits your era. “Meeching=cheap, petty.”

Gay Talk: a Sometimes (Outrageous) Dictionary of Gay Slang, by Bruce Rodgers. Paragon Books, 1979.

Originally published as The Queens’ Vernacular in 1972. “The principal aim of this book is to make available a dictionary of homophile cant…it records, without meaning to shock or anger, overheard pieces of living, fascinating slang”—introduction. Examples: “short roses=romance nipped in the bud,” “cornflakes=loveable, big, dumb farm boy.”

Mountain Range: a Dictionary of Expressions from Appalachia to the Ozarks, by Robert Hendrickson. Facts on File, 1997.

The introduction says that the entries contain both old and new terms, but use with caution for a historical novel, because not many of the entries contain date information. The title is self-explanatory, these are expressions found in the U.S. eastern mountains. “Raise sand=to create a disturbance,” or, “Dowie=sad, doleful.”

About the contributor: B.J. Sedlock is Lead Librarian and Coordinator of Metadata and Archives at Defiance College in Defiance, Ohio. She writes book reviews and articles for The Historical Novels Review, and has contributed to The Sondheim Review.