From Tales of Old: The Challenge of Novelising Age-Old Stories

by Elizabeth Jane Corbett

Historical fiction readers are accustomed to novels in which significant world events and their outcomes are already known, the writer’s challenge being to offer a fresh perspective, allowing the reader to see familiar events through different eyes. But what about when the novel is based on a well-known myth or fairy tale, one the reader has imbibed along with their mother’s milk? How does the writer make the well-worn come alive? What do they do with the magic and superstition? In what land and era do they set such an archetypal tale? I put these questions to three historical novelists, one of whom was Kate Forsyth, Australia’s ‘Queen of Fairy Tales.’

Historical fiction readers are accustomed to novels in which significant world events and their outcomes are already known, the writer’s challenge being to offer a fresh perspective, allowing the reader to see familiar events through different eyes. But what about when the novel is based on a well-known myth or fairy tale, one the reader has imbibed along with their mother’s milk? How does the writer make the well-worn come alive? What do they do with the magic and superstition? In what land and era do they set such an archetypal tale? I put these questions to three historical novelists, one of whom was Kate Forsyth, Australia’s ‘Queen of Fairy Tales.’

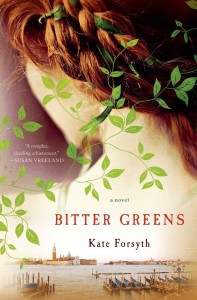

Bitter Greens, a dark sexual tale of obsession, madness, desire and resurrection, is based on the Rapunzel story. Forsyth loved ‘Rapunzel’ as a child and had always dreamt of writing it as a novel. However, it took her some time to realise it was never meant for children. Having come to this realisation, Forsyth also decided she didn’t want her Rapunzel novel to be set in a make-believe world. She wanted to ‘set it in the real world, in our world, where girls are still kidnapped and locked up in attics all too often.’

Having decided to anchor her novel in a historical time and place, I asked Forsyth how she determined the setting. ‘It took me a long time, but eventually I discovered that the story I knew of as “Rapunzel” was far older than the Grimms. I found the earliest known version had been written in the 1600s by Giambattista Basile, a man who was then working for the Venetian Republic. That set my imagination on fire, and so I began to envision the story set in late Renaissance Venice. However, Basile’s story was not the story I knew. I wanted to retell the tale that had meant so much to me as a child. I had to track down how the story travelled from Venice to Germany, and how it changed along the way. Again it took me a long time, but eventually I discovered the story of Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force, who wrote the version we know now of as “Rapunzel.” I knew at once I had to write about her – her life was full of drama and scandal and danger.’

Forsyth had found the three archetypal elements of her novel – maiden, prince and crone. With a self-professed fascination for folklore and supersititon, she infused each of their worlds with magic, giving her ‘fantasy elements’ a historicity by using spells and practices sourced from letters, memoirs and court transcripts. This is not the approach taken by Elizabeth Blackwell in her chilling first-person, retrospective retelling of Sleeping Beauty.

Told from the pithy viewpoint of Elise, a palace servant, While Beauty Slept takes place in an imagined kingdom, ruled over by a fictitious royal family. Blackwell has this to say about the decision: ‘I wanted the story to feel as if it had really happened, to real people. However, the story I envisioned didn’t fit into specific historical events, and I didn’t want to change the whole series of events so it would “fit” a particular royal family or kingdom.’ In the end, she decided not to specify the year or country, though she did use late medieval Europe and England as her inspiration. She wanted the setting to ‘feel familiar to readers of historical fiction, but also inspire each reader to create their own mental images, the way we all do when we first read a fairy tale.’

Blackwell may have used a ‘fairy tale’ setting for her novel, but her goal was to tell a version of Sleeping Beauty that didn’t include typical fantasy elements. ‘I thought of the fairy tale we all know as a story that’s been passed down for generations, changing along the way, and my book would be the behind-the-scenes, “real” explanation of what happened. I wanted to take those iconic events – the spinning wheel, the long sleep – and find a way they could be explained solely through human machinations, not magic.’

A recognisable historical setting, or once-upon-a-time, rationally explicable, or steeped in magic and superstition, these are the considerations of fairy tale retellers. But what about when your original story isn’t a fairy tale but a myth? A tale that, although fantastical, was believed to have its origins in historical events? I asked Judith Starkston, author of Hand of Fire – a novel told from the viewpoint of Briseis, priestess and lover of Achilles – how she handled this juxtaposition of the historical and mythological.

‘I scratched my head about what to do with a half-immortal main character, a goddess who enters the action and a priestess who believes her retelling of sacred stories brings about the fertility of fields and herds. Then I realised the solution to integrating the mythology and the history was rising out of the historical record. If my Bronze Age characters believe that gods walk among them and they, as mortals, have genuine contact with divine powers, then all I had to do was allow my characters to act just the way they would have – and the “mythological” or fantasy elements would naturally integrate into what we, from the modern perspective, think of as the “real” elements.’

It would seem that combining historical and fantasy elements in unique ways is the key to making well-known stories come alive as historical fiction. Kate Forsyth also believes an element of surprise is essential. ‘I think surprise is the magic ingredient of all good storytelling. I am always thinking to myself, how can I best surprise the reader? I think this is even more important in a fairy-tale retelling, because the story’s structure and motifs are so familiar to most readers.’

For Blackwell, finding a surprise ending came up late in the editing process. ‘My original draft ended very much as the fairy tale does, but I’ve since come to realise that it was a bit of a let-down. I’d been taking liberties with other parts of the story, so why be completely predictable at the end? If you’re going to take on a very familiar story, you owe it to readers to rework that story in creative ways – whether it’s through genre or tone or style.’

No exploration of fairy tales would be complete without discussing the helpless princess stereotype that typifies many Disney-type retellings. Is this a necessary element of the genre? How do you make stories that are dependent on ‘female servility, immobility or even stupor, and on princely rescue’1 relevant to the modern reader? For Starkston, whose main character was a prisoner of war and lover to the man who had slain her father and brothers, the answers came from the historical record. ‘I figured if there was a psychologically believable answer, it lay in who Briseis was before she met Achilles. Some people suggested early on, that it was a case of ancient Stockholm Syndrome, but since Achilles is the warrior who questions why they are fighting and is generally in search of the meaning of life, I couldn’t see him as a brainwasher and I went for a deeper answer.’

Starkston based her Briseis on descriptions of a healing priestess found on cuneiform tablets, making her protagonist a healer and a singer of sacred tales – activities Achilles was famous for along with his fighting prowess. ‘I had to spend a fair amount of time building this world with this “job” of healing priestess for my modern audience because it is so exotic to us, but once I showed Briseis in action as a healing priestess, the groundwork for believing she could connect with Achilles was there in storage for when they actually cross paths so disastrously.’

The solution was not so easy for Blackwell, writing from the point of view of a powerless medieval servant. Although set in an imaginary time and place, she was determined her protagonist’s characterisation would be historically appropriate. ‘It’s simply not realistic to create a female character in the Middle Ages who has a contemporary, girl-power mindset. Most women of that time accepted that they were subservient to men, just as most servants accepted that they were subservient to their masters. The challenge for writers is to make those characters compelling to modern readers, despite those vast differences in how we view our place in the world.’

By contrast, Forsyth rejects the version of Rapunzel in which a subservient woman is rescued by a handsome prince. ‘It always makes me cross when people call Rapunzel the “passive princess” waiting patiently for her prince. She is not a princess, she does not wait patiently but rather sings with all her heart and soul and so draws the prince to her, and she is the one that saves the prince, not the other way around. She is a mythic figure of feminine power who frees herself and then heals the blinded eyes of the prince. It is true that she is held in stasis and immobility in the first part of the story, but never forget that she escapes her tower at the end. That is the whole point of the story.’

These three different writers use setting, fantasy elements, and strong female characters to powerfully re-create ancient tales. Add to this research, an ability to adopt an historical worldview, a willingness to add surprise elements, and retelling fairy tales becomes not so different to writing historical fiction. Moreover, as Forsyth reminds us, the appeal is timeless. For ‘it is not only women who are held captive by the metaphorical towers of society. Men are, too. Fairy tales are a window into the human psyche, and hold wisdom for us all.’

References:

1. Atwood, Margaret. (2002) “Of souls as birds,” in Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore their Favourite Fairy Tales. New York: Anchor Books, p. 22.

About the contributor: ELIZABETH JANE CORBETT works as a librarian, teaches Welsh, and blogs at elizabethjanecorbett.com. Her short story, “Beyond the Blackout Curtain,” won the Bristol Short Story Prize. An early draft of her historical novel, Chrysalis, was shortlisted for a Varuna manuscript development award. It has been re-drafted as The Storyteller, a novel with a fresh spin on Welsh fairy tales.

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 71, February 2015