Authentically Unfamiliar: Melissa Bissonette on Alexander Manshel’s Writing Backwards

WRITTEN BY MELISSA BISSONETTE

From its beginnings, historical fiction has struggled for respectability. In 1814, John Wilson Croker, an early literature gatekeeper who preferred his history raw, took pains to distinguish Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley from the rest of the genre, which was “mere romance, and the gratuitous invention of a facetious fancy” – that fancy being, more often than not, a female one, concerned with costumes more than truth. He detested works “in which real and fictitious personages, and actual and fabulous events are mixed together to the utter confusion of the reader, and the unsettling of all accurate recollections of past transactions.”1 Even as the novel gained respectability over the 19th century, historical fiction, as a category, largely lagged behind. Until recently, if a bookstore shelved The Scarlet Letter, War and Peace, or Beloved among historical fiction, pearls would be clutched to tweedy bosoms.

From its beginnings, historical fiction has struggled for respectability. In 1814, John Wilson Croker, an early literature gatekeeper who preferred his history raw, took pains to distinguish Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley from the rest of the genre, which was “mere romance, and the gratuitous invention of a facetious fancy” – that fancy being, more often than not, a female one, concerned with costumes more than truth. He detested works “in which real and fictitious personages, and actual and fabulous events are mixed together to the utter confusion of the reader, and the unsettling of all accurate recollections of past transactions.”1 Even as the novel gained respectability over the 19th century, historical fiction, as a category, largely lagged behind. Until recently, if a bookstore shelved The Scarlet Letter, War and Peace, or Beloved among historical fiction, pearls would be clutched to tweedy bosoms.

The anxiety, the need to draw a thick red line between what qualifies as “literature” and what qualifies as “historical fiction” has not changed, although where that line is drawn certainly has. The point of balance between fiction and facticity continually shifts, inciting the outrage of the likes of Croker and some 21st-century school boards. Since authenticity grounds historical fiction, the battle has often been precisely what our truth is – whose truth, which history. In an essay from 2023 titled “Why Historical Fiction Matters,” Steven Mintz wrote, “Historical fiction isn’t history, but it can reveal the historical truths that lie beyond the evidentiary. It is an expression of our ongoing, unending quest to understand our forebears who formed us, scarred us and, to a certain extent, freed us.”2

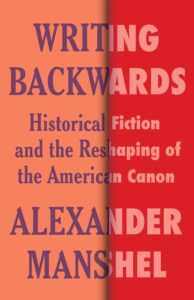

Even before the pandemic, Megan O’Grady wrote in the New York Times that historical fiction seemed suddenly more urgent. “Making sense of our lives and of the unfathomable world in which we find ourselves has necessitated an understanding of what has come before–a clarification of the game and its stakes but also its rules and positions. A new kind of historical fiction has evolved to show us that the past is no longer merely prologue but story itself, shaping our increasingly fractured fairy tales about who we are as a society.”3 Alexander Manshel, author of Writing Backwards, begins with that “belief in fiction’s ability to access, reconstruct, and even recuperate the historical past” (page numbers from Writing Backwards, 19).

Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon (Columbia University Press, 2023) addresses a broad public audience. Manshel charts a rise in the prestige of literary historical fiction, using the shortlists for American literary prizes as his gauge. “In the United States,” he writes, “literary fiction has never been more historical—nor historical fiction more literary—than it has been over the last forty years” (17). While historical fiction accounted for about half of all novels shortlisted for a major American prize between 1950 and 1979, and up to two-thirds of those lists by 1980, it reached “a whopping 80 percent [of all shortlisted novels] in the first decade of the twenty-first century alone” (4).

And in these last decades, writers of color have been on these lists in greater numbers. “In some ways,” Manshel told me, “the works of historical fiction that are being most celebrated today are by writers of color working to amend or even disrupt and rewrite the historical record as we understand it.”4

Writing Backwards reads the work of many celebrated writers of color of the last twenty years, including Yaa Gyasi (Homegoing), Colson Whitehead (The Underground Railroad, Nickel Boys), Viet Thanh Nguyen (The Sympathizer), Margaret Wilkinson Sexton (A Kind of Freedom), and Min Jin Lee (Pachinko). Each explores histories more frequently told from a white vantage point, whether sympathetic or not. To some extent, these writers leverage our knowledge of unresolved issues in the present to complicate the reader’s desire for positive endings in the fiction. Colson Whitehead’s structural choices, for example, “heighten the pathos of historical pain, but it also emphasizes the limits of historical fiction as a means of addressing the challenges of the present. History may provide a clear analogy, but Whitehead’s historical fiction reminds us that only looking backwards means that the crucial moment of action… will always have already passed…. The moment to ‘enlist’ or intervene is always already over” (161-2). In this and other instances, Manshel draws attention to novels that have destabilized some of the more conservative, nationalistic tendencies of prestige fiction.

While other writers have addressed the fundamentally conservative impulse behind the domination of the World War II novel, Manshel considers its “truly remarkable concentration of literary prestige” part of an ongoing “cultural struggle over which war emblematizes Americanness in general. Is it World War II and the Greatest Generation fighting against Nazi forces? Or is it the Civil War, a war fought over enslavement, where Americans are fighting Americans? Is it the Vietnam War, a proxy war where the US is not at all the hero?” Complicating the narratives and aesthetics of prize-winning WWII fiction, “Black, Asian American, Latinx, and indigenous writers have been working to amend the public memory” to include the ways their communities participated in or were excluded from the heroism of the Greatest Generation.

Manshel links the significantly increased recognition of minority or marginalized writers on the literary prize shortlists to the rise in prestige of historical fiction. On those lists, novels by writers of color are far more likely to be historical fiction than are novels by white writers (for example, 75% for Black writers and 90% for Indigenous writers, compared to about 50% for white writers). One positive interpretation of this dynamic looks to the shift in our understanding of racism(s) as systemic. To seek to understand inequality, now, is necessarily to seek to understand how it came to be.

The multi-generational novel epitomizes that project of reading the present through the past. “If we’re looking to literary fiction to teach us about the historical past, to recover lost histories, and to recognize people that we’ve previously overlooked, the multi-generational family saga does it all,” Manshel told me. Bestsellers Homegoing and Pachinko have plenty of company, including Namwali Serpell’s The Old Drift (2019) and, most recently Claire Messud’s This Strange Eventful History (Fleet, 2024, see review in this issue of HNR), which uses the author’s own family tree to explore nationality, belonging, and displacement. The novelist’s choice to proceed in linear chronological order (as does Gyasi and Lee) or alternate among them (as does Sexton and the Apple TV version of Lee’s book) can imply dramatically different relations “between narrative progress and political progress” (196), advancing and repeating, recovery and relapse.

To return to the problem Whitehead poses, that whatever happy ending the reader wishes for is tempered by the realities of both past and present, these books challenge the reader to learn and to empathize despite what we may know or think we know. (Though I remember seeing the film Titanic in a movie theater in 1997 and overhearing another woman complain, “I wouldn’t have come if I’d known it had a sad ending.”) Is this a version of the collision of facticity and fiction that all historical novels wrestle with? Authors’ notes frequently provide bibliographies and detail which letters are transcriptions and which fictions, though the novel itself must blur that distinction. The New Yorker writer Jennifer Wilson praised Messud’s novel quite specifically for its reliance on a family history written by her grandfather. “Messud has used that document to craft something more interesting than a historical novel: a novel about history and the stories we tell ourselves about the role we play in it.” 5 To some extent, that self-consciousness about history pervades historical fiction, rather than being a tool by which to rise above it.

The “authentic fiction” paradox is at the core of historical fiction. The details have to be second-hand. The HNS website states that “To be deemed historical (in our sense), a novel must have been written at least fifty years after the events described. Or written by someone who was not alive at the time of those events, and therefore approaches them only by research.” 6 Scott’s Waverley; or, ‘Tis Sixty Years Since set the standard (60 years, roughly a man’s life expectancy) and the Walter Scott Prize continues to enforce this limit. Scholar James F. English, whose work dovetails with Manshel’s, capped his exploration at 20 years before publication. Others will say the work must be set before the time of the author’s birth. These calculations merely attempt to quantify the distance which makes the world alien. Jerome De Groot speaks of the fundamental strangeness of historical fiction: “The historical novelist … explores the dissonance and displacement between then and now, making the past recognisable but simultaneously authentically unfamiliar.”7 Authentically unfamiliar.

Manshel closes his book with an intriguing discussion of the novel of “recent history,” books like Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being (2013), which “betray a historical self-consciousness” and which are “less interested in fictionalizing the present than they are in using fiction to cast the recent past as historical with a capital H” (206). These are deeply invested in the literal mediation of events through the CNN chyron, newspaper headlines, and social media posts. Recognizable but simultaneously authentically unfamiliar.

“As readers,” Manshel concludes, “we are always interested in the end of the story. But of course, as we’ve learned, there is no end of history. We’re always living in the middle of history.”

References:

- The Quarterly Review, July 1814.

- “Why Historical Fiction Matters: The History that Lies Behind Pure Fact.” Inside Higher Ed, March 5, 2023.

- “Why Are We Living in a Golden Age of Historical Fiction?” New York Times, May 7, 2019.

- Interview with Alexander Manshel, May 2, 2024.

- Wilson, Jennifer. “Paradise Lost: The search for a home that never was in Claire Messud’s new novel.” The New Yorker. May 13, 2024, 63-65.

- https://historicalnovelsociety.org/guide-our-definition-of-historical-fiction/

- The Historical Novel. Routledge, 2010, 3.

About the contributor: Melissa Bissonette lives in western NY where she teaches 16th-19th century theater, poetry, and fiction. Her novel Daughter of the Law, set in 17th-century London, traces the biography of Frances Coke Villiers.

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 109 (August 2024)