A Victorian Tragedy: Elizabeth Laird on The Prince who Walked with Lions

by Lucinda Byatt

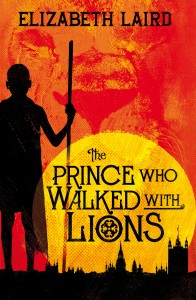

An award-winning author of several novels, both historical and not, for children and young adults, Elizabeth Laird has travelled and worked in many countries, including Ethiopia where, in the late 1960s, she remembers seeing Emperor Haile Selassie standing with a full grown lion beside him as part of the royal entourage. Her book, The Prince who Walked with Lions (Macmillan Children’s, 2012) has already been selected by young Scottish readers for the shortlist of the Scottish Children’s Book of the Year Award, to be announced in March. It tells the story of Prince Alemayehu, the young son of the defeated Emperor of Ethiopia (or Abyssinia as it then was), who was brought back to Victorian Britain. The whole nation became fascinated by Alemayehu and he “stole the heart of Queen Victoria”. At eighteen, his death shocked and saddened many, including the queen: the prince is buried in St George’s chapel, Windsor, although efforts are now being made to secure the return of his remains to Ethiopia.

An award-winning author of several novels, both historical and not, for children and young adults, Elizabeth Laird has travelled and worked in many countries, including Ethiopia where, in the late 1960s, she remembers seeing Emperor Haile Selassie standing with a full grown lion beside him as part of the royal entourage. Her book, The Prince who Walked with Lions (Macmillan Children’s, 2012) has already been selected by young Scottish readers for the shortlist of the Scottish Children’s Book of the Year Award, to be announced in March. It tells the story of Prince Alemayehu, the young son of the defeated Emperor of Ethiopia (or Abyssinia as it then was), who was brought back to Victorian Britain. The whole nation became fascinated by Alemayehu and he “stole the heart of Queen Victoria”. At eighteen, his death shocked and saddened many, including the queen: the prince is buried in St George’s chapel, Windsor, although efforts are now being made to secure the return of his remains to Ethiopia.

Laird’s highly evocative novel is a wonderful read: she focuses on Alemayehu’s life at his father’s mountain-top court in Abyssinia and later on his school years in England. I began by asking about her research.

“The British campaign in 1868 against the Emperor Tewodros of Ethiopia is well documented in official reports and personal memoirs. After his defeat, the Emperor put his wife and child into the care of the British before he committed suicide. The young queen died during the journey to the coast and little Prince Alemayehu established a strong friendship with the eccentric and dashing British captain, Charles Speedy, who was put in charge of him.”

Charles Speedy was “a great barndoor of a man” and he became very attached to the young prince. Laird writes that “During Alemayehu’s early years away from Ethiopia, he was happy with the Speedy family and his plight aroused great sympathy in Britain. Crowds followed him wherever he went.” However, Speedy’s subsequent posting abroad meant that Alemayehu was sent to Rugby where he had to adapt to the totally alien world of an English boarding school. Laird adds that, “Captain Speedy’s mother-in-law, Cornelia Cotton, wrote a short memoir of his childhood in Britain, and Queen Victoria mentioned him affectionately in her diaries. Little is known of his time at Rugby, and I scoured the school records and in-school magazine to pick up what clues I could. Official reports say that he was popular and admired for his prowess in sport, but British schools at that time were notoriously tough. It can’t have been easy.”

I also asked Elizabeth whether historical fiction can inspire young people to study history and also to become interested in historical subjects and topics that are not on the school curriculum. With a resounding yes, she agreed that “The study of history is vital if we are to learn from the mistakes of our forebears. The value of good fiction is that it enables us to put on other pairs of shoes and walk around in them for a while. This is how we develop empathy, crucial to the maturing process. Historical fiction enables readers to imaginatively enter into the past and learn the lessons of history. Once the imagination is fired up, learning history becomes no longer a chore, but a delight.”

Elisabeth certainly does not shy away from controversial and difficult situations involving extreme poverty and political marginalisation: her books Garbage King, A Little Piece of Ground and Oranges in No Man’s Land are examples. She was keen to add that over the past two years, in collaboration with a colleague, she has created a website www.ethiopianfolktales.com to preserve the three hundred stories she collected all over Ethiopia. Now, she says, “we’re attempting to publish English readers for Ethiopian schoolchildren online too.”

When I asked her about future plans, she shied away, saying “my fifth historical novel is in the pipeline, but I’d rather not talk about it, in case the ideas fly away out of my head!”

About the contributor: Lucinda Byatt translates historical nonfiction from Italian into English and teaches Italian Renaissance history. She writes and reviews regularly for the Historical Novels Review and can be found blogging at textline.wordpress.com.

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 63, February 2013