Reflections of Identity & History: Kristen McQuinn Discusses Hall of Mirrors with John Copenhaver

WRITTEN BY KRISTEN MCQUINN

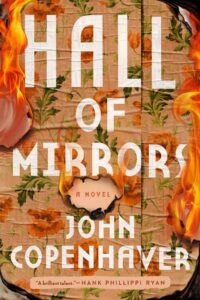

The 1950s were a complex time, filled with political intrigue and deep social and moral imbalances. This is the tumultuous backdrop for John Copenhaver’s latest novel, Hall of Mirrors (Pegasus Crime, 2024), a thoughtful reflection of identity, politics, and the human experience.

The 1950s were a complex time, filled with political intrigue and deep social and moral imbalances. This is the tumultuous backdrop for John Copenhaver’s latest novel, Hall of Mirrors (Pegasus Crime, 2024), a thoughtful reflection of identity, politics, and the human experience.

Copenhaver set Hall of Mirrors in the McCarthy era, following the timeline established in his previous post-WWII novel, The Savage Kind (Pegasus Crime, 2021), featuring the same main characters, Judy and Philippa. Copenhaver explains that he had more to tell about their story and wanted to follow them in their growth from teenagers to young women. He says that the McCarthy era was “a particularly difficult time to be an independent-minded woman, especially if you’re queer and, in Judy’s case, mixed race.”

Researching and writing about this period uncovered some unique challenges, particularly those facing the LGBTQ+ and Black communities. Copenhaver immersed himself in the socio-political climate of the 1950s, uncovering the intricate ways in which government policies shaped societal attitudes. The McCarthy era is indelibly marked by government-sanctioned discrimination against Black and queer individuals, which bled over into society as a whole. Copenhaver notes, “The McCarthy era, from overt political figures grasping for power like McCarthy to the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, led to the perpetuation of discriminatory ideologies that still linger.” It is in the space left by these attitudes that Copenhaver is able to explore their continuing impact on modern society. He says, “These attitudes still echo today, making it a rich and relevant setting for my story.”

Copenhaver deftly manages the delicate task of balancing historical accuracy with creative storytelling. His story incorporates many of the dark facets of the McCarthy era and how various government agencies acted while simultaneously revolving around a domestic setting through the private lives of Judy and Philippa, as well as those of Roger and Lionel, the novel’s murder victim and suspect. He explains that this balance was crucial to create an authentic and engaging narrative. The domestic side of the novel really is where the narrative shines, allowing readers a glimpse into the minds of the characters.

The book’s title itself gives readers a deeper perspective and acts as a portal into the themes within, with the concept of reflection and doubling at the forefront. The society that Judy and Philippa navigate is fraught with double standards and questions of identity. Copenhaver elaborates, “I’ve always been interested in mirroring and doubles, a consistent theme in film noir. In this novel, I explore several doubles: Judy and Philippa, Roger and Lionel. Opposites attract, and love aligns, yet mirrors also suggest vanity and the question of identity.”

Identity is further explored in the representation of LGBTQ+ characters, which are a cornerstone of Copenhaver’s writing. Thanks to Copenhaver and other contemporary writers, these characters are being written back into historical fiction. He says that LGBTQ+ representation in his work is an intentional correction of invisibility and, “It’s about enjoying a twisty mystery while considering historical representation.”

The theme of “passing” is also central the narrative. Judy has spent her life passing as a white woman, though in reality she is biracial. Passing has been a complex issue for decades, having its origins in the colonial and antebellum South eras. Initially, the practice of racial passing was used as a means of escaping slavery, but it continued in the post-Reconstruction era as a strategy to avoid systemic racism. Passing carried on into the 1950s, both in terms of racial passing as well as passing as straight for members of the queer community, again as an attempt to escape from the racism and homophobia of the time. Copenhaver notes that passing also “raises questions of identity and agency, highlighting the moral imbalances of societal norms.”

Moral imbalances are further explored through the lens of the political landscape of the 1950s. This time period was marked by the Red Scare and Jim Crow laws which also targeted LGBTQ+ individuals. The merest hint of accusation could be enough to destroy an entire life. Copenhaver reflects, “The Lavender Scare, a subset of the Red Scare, led to the persecution of gays and lesbians in government roles, driven by fearmongering and power dynamics.” Roger’s firing from his job at the State Department and Lionel hiding his true relationship with Roger from the police during their investigations are reflections of the Lavender Scare and systemic racism in action.

While acknowledging social progress since then, Copenhaver questions the true extent of change. Through the characters’ experiences, he urges readers to critically analyze fear-driven narratives, emphasizing the importance of understanding historical contexts to foster meaningful change.

When dealing with heavy themes, a reflection on grief and loss is only natural. Copenhaver’s personal experiences with grief shape his writing. He candidly discusses the impact of his father’s early death, stating that this formative experience forced him to reflect on loss, mortality, and why bad things happen. He describes his writing as “inherently dark yet affirming, reflecting the complexities of life.”

Copenhaver further notes, “Exploring grief allows for a deeper understanding of human experiences, showcasing the resilience and affirmation that coexist with sorrow.” Philippa, Judy, and Lionel embody various aspects of grief and resilience as they experience the loss of loved ones, of their security, livelihood, and identity. They also are the embodiment of perseverance, carrying on despite hardship and persecution. As Copenhaver’s vibrant, complex characters demonstrate, it is during difficult times that people’s true selves emerges.

Hall of Mirrors emerges as a nuanced exploration of identity, politics, and human resilience within the McCarthy-era, as well as holding up a mirror to our modern lives and challenging us to do better. Copenhaver’s captivating narrative encourages readers to reflect on historical legacies, LGBTQ+ representation, and the enduring quest for identity and belonging.

About the contributor: Kristen McQuinn has degrees in medieval literature from Arizona State University. She works at University of Phoenix overseeing general studies faculty and teaching literature courses. She lives in Phoenix with her teenage daughter.

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 109 (August 2024)