Launch: Steve Wiegenstein’s Land of Joys

INTERVIEW BY MALLY BECKER

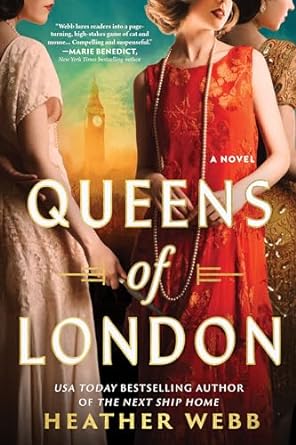

Steve Wiegenstein is the author of five books, most recently Land of Joys, a historical novel that takes place at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and in the fictional Ozarks village of Daybreak. His short story collection Scattered Lights was a finalist for the 2021 PEN/Faulkner Award in Fiction, and he received the Missouri Author Award from the Missouri Library Association in 2022. He also writes and blogs about rural and Ozarks issues.

How would you describe your book and its themes?

Land of Joys follows a group of Ozarkers as they travel to the St. Louis World’s Fair to be put on exhibit as “authentic hillbillies,” following the publication of a popular novel that romanticizes life in the hills. Charlotte Turner, the matriarch of the village, and her granddaughter Petey, who is enthralled by the promise of modernity exemplified by the Fair, have to navigate threats back home and at the Fair, as they cross from the old century into the new.

What inspired you to write Land of Joys?

What inspired you to write Land of Joys?

At one point in my writing journey, I was struck by how many books focused on romantic love, whether found, lost, or failed in whatever combination, and how comparatively few books dealt with other types of love at their center. One thing I’ve seen over the years is the incredibly powerful love between a grandparent and grandchild. It’s a very different kind of bond than between people of similar ages, because one person is just coming into her or his life and the other person is growing nearer to its end. And one person doesn’t have much knowledge or experience of the world, and the other person has perhaps too much. So the flow of feeling is very different than in other kinds of love. So I decided to try to make a grandparent/grandchild relationship central to this story, because it’s something I felt bound to portray, and I wanted to see how things would hinge based on that.

What role does the St. Louis Fair of 1904 play in your novel?

Like most people, my impression of the St. Louis World’s Fair was formed by Meet Me in St. Louis, the wonderful Vincente Minnelli/Judy Garland movie from 1944. It wasn’t until I started researching it that I realized the Fair was an immense and complicated event. It was a massive display of technological innovation, a significant tourist destination (for the seven months of its existence), an orgy of American self-celebration. It was also, let’s face it, a celebration of the idea of white supremacy, an event in which so-called “primitive” people were set up in exhibits for white people to stroll past and feel superior to. Even people of color from within the United States were not made welcome at the Fair. It was like a huge magnifying class that showed the American character of the time in all its elements, and it was irresistible to portray. In the novel, the rural characters who come to the Fair are meant to be intimidated by its size and grandeur, and that’s a reflection of the intent of the Fair’s creators. The idea was to wow people, to leave them gasping at the dominance of American technology and power, and it succeeded at that goal very well.

Who’s your favorite secondary character?

Charley Pettibone. Charley first arrives in my novel series in the first book, Slant of Light, as a gabby and rather smart-alecky fifteen-year-old, then he goes through a very dark period in This Old World, the second book, after he has gone off to war and come back embittered. By this book he’s heading into old age, and he’s still gabby and somewhat smart-alecky, but he has decades of life behind him. Every time Charley shows up in a scene, it’s a real gift to me as a writer because I can just get into Charley’s head and let him go. Interesting things will always happen.

You were raised in the eastern Missouri Ozarks. Did your family history or journalism background find its way into your story?

Oh, very much so. My parents were country people. They grew up on adjoining farms, and one thing they taught me was respect for your roots. My dad was not a highly educated person, but he was one of the world’s great noticers. Whenever I went out with him, I came back knowing something that I hadn’t known before. One character from my family history that makes it into my books is the Civil War guerrilla Sam Hildebrand, who terrorized my home area during the war. We had a family story about Hildebrand murdering my great-great-uncle, and when I researched the era and found his autobiography, he confirmed the family story in detail. So I felt that I had to include Sam Hildebrand in the story just to balance the scales after all those years. My newspaper years yielded me a wonderful range of people to interact with, from community leaders to criminals (and sometimes both categories in the same person).

What did you admire the most about the Ozarks in the early 20th century? What did you find most troubling?

What did you admire the most about the Ozarks in the early 20th century? What did you find most troubling?

Wendell Berry likes to say, “Rural America is a colony, and its economy is a colonial economy.” Many people idealize rural life but also misunderstand and fear it, and wouldn’t dream of living in a small town or on a farm. Having grown up on a farm myself, and coming from a long line of farmers, I see things from a different perspective. Every generation of Americans gets a little farther from rural life, which is truly a pity. The issues we see today with the degradation of the land, the industrialization of farming, the increasing divide between a dwindling, aging rural population and the distant urban and suburban population that depends on them for food, these issues all have roots in the nineteenth century. My grandfather’s reminiscences of growing up at the turn of the twentieth century were ones of incredibly hard physical labor but also a kind of stubborn independence that few people get to experience. It is indeed a lost era, one we should get to know better.

What inspired you to write historical fiction?

I have been writing since my twenties, but always short pieces. Short stories, newspaper and magazine articles. I had written a novel early on, but it wasn’t any good. But in my fifties, I had an insight while watching the news, of all things. It was a story about the Iraq war: an occupying army, incredible factionalization, the ever-present threat of terror, the sense that nobody could be trusted, neighbors betraying neighbors, and so forth. And I thought: that’s just like Missouri during the Civil War! All of a sudden the whole idea came to me to use a small Missouri Ozarks village as a microcosm for the entire American experience through history. And I’ve been off to the races ever since.

What is the last great book you read?

Annalee Newitz, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age.

![]()