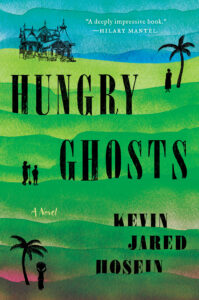

The Phantoms of Choice: Hungry Ghosts by Kevin Jared Hosein

artwork credit: Ecco

BY ELISABETH LENCKOS

“This is your place in the world. And there is no other world out there but this one.” — Kevin Jared Hosein, Hungry Ghosts

When Kevin Jared Hosein wrote his novel Hungry Ghosts (Ecco, 2023), set in Trinidad in the 1940s, he kept the ancient Indian texts, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana by his side. “The majesty and poetry of the writing had some influence on [my] prose,” he explains. “The most direct influence was, of course, the titular Hungry Ghosts in East Asian mythology—forever wanting, forever insatiated.”

Like those hungry ghosts, the inhabitants of Bell village are in search of fulfilment, prosperity, upward mobility, a better life. The main protagonists reside in the barrack, which is home to the labouring family the Saroops: Hans, Shweta, and their son Krishna. Not far from the barrack rises the manor house of Dalton and Marlee Changoor, rich landowners who live in considerable luxury and splendour. But the source of Dalton’s wealth is doubtful, and one day, he goes missing. When a ransom note appears, his wife decides not to pay. Instead, she employs Hans to guard the property and pays him a generous income. It doesn’t take long before tensions rise between manor and barrack, and a series of tragic events changes the community in lasting ways.

Hungry Ghosts presents readers with a gripping portrayal of social conflict. It is also a coming-of-age story, which opens with the blood oath between four boys who have no way of knowing how the promise they make to one another will impact their future lives. In addition, Hungry Ghosts spins a fascinating historical narrative, charting within the culture of Trinidad in the 1940s the influence of subsequent waves of immigrants—(African) slaves to (Indian) indentured labourers—and the different religions and ancient belief systems they bring with them to the island.

In this regard, the novel seems to harken back to the great Caribbean classic, A House for Mr Biswas (1961) by V S Naipaul. Naipaul’s hero, too, is Indian-Trinidadian and Hindu, tested in his ethics by this marriage into the rich Tulsi family. When I asked Hosein whether A House for Mr Biswas inspired his novel, his answer proved intriguing. He stated that although Naipaul’s classic did not cross his mind during the research, planning, and writing of Hungry Ghosts, he realised that “the very seed of Biswas is echoed… in a dialogue with Robinson [a Christian character in Hungry Ghosts], where he speaks of a man without a house, without a household, is nothing in this society.”

author photo by Mark Lyndersay

Interestingly, Hosein’s comment places Hungry Ghosts in the tradition of the Great House Novel, which in the postcolonial era includes such seminal texts as Edna Brian, House of Splendid Isolation, André Brink Imaginings of Sand, Rosario Ferré, The House on the Lagoon, Damon Galgut, The Promise, and Kazuo Ishiguro, Remains of the Day. Moreover, Hosein’s protagonist Hans resembles Ishiguro’s Stevens, the butler in Remains of the Day, who serves his master without questioning and pays the price when his employer turns out to have fascist leanings. Similar to Stevens, so Hosein told me, Hans lacks self-awareness: “He accepted the bigotries of the schoolmaster, store clerks and constables—even to the detriment of his wife and child…He tried to split himself between two masters… He mistook submission for strength. Though the novel delves deeply into choice, or the phantom of choice, Hans experienced a personal desperation that was only made worse by dangling an illusory world in front of him. At a point, he became devoted to a foundation-less dream, thus sealing his fate.”

Hans’ son Krishna, on the other hand, is a rebel. As Hosein explains, “The blood oath, hallucinatory trips and teenage gang warfare that Krishna and his friends partake in are not only acts of rebellion against sacred rites and frameworks but against societal expectations…. It is, in their own way, creating their own traditions as if to reject the beliefs of the world that surrounds them. Krishna is one of the only main characters in the book who does not wish for upward mobility—he is mostly satisfied with his family and living conditions until talk of money and a new house in Bell Village comes up. He simply wishes to live and let live. After all, he is only a child. However, that proves to be a notion that is impossible in his universe.”

As Hosein’s comments on Krishna indicate, Hungry Ghosts is not afraid to tackle philosophical issues. The question of free choice, what Hosein calls ‘the phantoms of choice,’ informs the novel in exciting ways: “When plotting and writing Hungry Ghosts, I was focused on giving the characters’ gritty split-second decisions that could likely change the trajectory of their lives, and those around them. Marlee jumping into the back of Dalton’s pickup as a teenager; the twins’ father to join the pirates; Hans’s mother to stay with her children instead of leaving. I’d been listening to relatives tell stories of the Indian indentured who came to Trinidad, and they had spoken of the likelihood that some of our ancestors might have simply signed up at the very last minute to avoid zamindars (tax-collecting land-owners) or to elude punishment for crimes. Split-second decisions again, as if it makes very little [sense] to plan ahead when being held in such downtrodden and desperate conditions… Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean that there was absence of ambition.”

Hosein is passionate about the history of Trinidad, especially its emergence from under the shadow of colonialism: “… [T]he basic truth was that when the Indian indentured arrived in Trinidad, their food and rituals and styles of dress were seen as alien to the recently emancipated Afro-Trinidadians. The colonial authorities… prevented the locals from coming together during community events out of fear of unrest and uprising—the unfortunate climax of a rebellion against this being the Hosay Massacre in 1884, where Hindus, Muslims and Christians met with volleys of British bullets. The dead were quickly buried in trenches and the Governor was subsequently absolved for this. In the 1940s, at the time of Hungry Ghosts, there must have been harmony—even if it were forced harmony—among the faiths. At that point, I think we would have realised that we were all brought here with no intention of ever being a civilisation on this island. We had to trust ourselves and each other to make it so. But there still would have been bastions of prejudice and exclusion—Bell Village being my interpretation of such.”

He is proud to be a Caribbean author. “I also consider myself greatly fortunate to be based in my home country,” Hosein adds. “Caribbean traditions, and more specifically Trinidadian, embody the spirit of a warm union. Union, as you would rarely find a Caribbean citizen in disconnection with their surroundings, whether it be through in community or nature or the various home-grown artforms. The cuisine, the tunes, the use of Creole English are all unions of instruments and measures and gauges, from multiple ancestries and heritages. Alas, sometimes to be Caribbean means to be in love with something that was destined to be wounded—simultaneously and paradoxically trying to hide the scars and be prideful of them.”

When asked whom he considers to be his forebears, Hosein has this to say: “It may appear vain for me to say that I do not seek to follow in anyone’s footsteps—though I only say this because the number of writers that have fully based themselves on their rocks while echoing the words of those rocks has been slim. This has already been set to change. It is through modern technology and ease of access that a writer today, of little means of scholarship and migration, can attempt to infiltrate this world of literary agents and editors from their Caribbean sunlit living room. While I hold high admiration for the range and ambition of the works of many olden and contemporary Caribbean authors, I seek to create stories that immerse, entertain and pay homage to the country and people that educated me.”

In conclusion, Hosein reveals that his idea for Dalton Changoor’s mansion, and Dalton himself, originated in the ‘Friendship Hall’ estate that was formerly located in Chase Village, Trinidad. He discloses that he was fascinated by “the eddying mix of Hindu iconography” within the house, as well as by the legend associated with its owner, a Scot who went half-mad and willed the house to one of his servants’ daughters. Since demolished, ‘Friendship Hall’ came to signify in Hosein’s imagination not only a place of enigma and intrigue—the perfect setting for Hungry Ghosts—but a personification of human “mislain and isolatory concepts of wealth and satiation.”

A paean to Hosein’s beloved Trinidad and the people who founded a civilization on the ruins of the former colonial empire although they arrived on the island under hostile and adverse conditions, Hungry Ghosts seems poised to become a modern Caribbean classic.

About the contributor: Elisabeth Lenckos reviews and writes for the Historical Novel Society. A member of its Social Media Team, she posts and tweets to its members on Wednesdays. She is at work on a novel about a 20th-century German Jewish family.