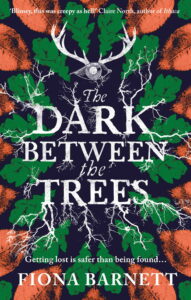

Launch: Fiona Barnett’s The Dark Between the Trees

INTERVIEW BY REBEKAH SIMMERS

Fiona Barnett lives in Edinburgh and grew up near the New Forest with stories of Roundheads and Cavaliers, and ancient secrets in the heart of the woods. She has podcasted on the British Civil Wars, and her short fiction has appeared in Haunted Voices: An Anthology of Scottish Gothic Storytelling. Rebekah Simmers interviews her on the release of her novel, The Dark Between the Trees, a Gothic thriller set in 1643.

How would you describe this book and its themes in a couple of sentences?

Five women led by a historian go into a remote wood in northern England, looking for traces of a group of soldiers who disappeared in it during the English Civil War in the seventeenth century. Only two of the soldiers were ever seen again, and their stories about what happened to them make no sense—stories of shifting landscapes and of a creeping shadow that seemed to follow them through the trees. But whatever it was that found those soldiers, it still walks the woods…

What life experiences have shaped you as a writer or affected how you approach your stories?

What life experiences have shaped you as a writer or affected how you approach your stories?

I’ve never been an academic historian, but I have occasionally gone down an extremely in-depth historical rabbit hole. A few years ago I researched and presented a podcast on the British Civil Wars, and it really ignited my enthusiasm for the whole period. In particular, I got very interested in ordinary people and the strange things that sometimes happened to them, which are only in the historical record because someone alluded to them once as an aside in a letter. You can get a very good story out of asking, “Hang on a minute, what bizarre stuff was going on over there?”

A Gothic thriller! Can you give us a brief explanation of what that means?

It’s hard to strictly define Gothic fiction, but I think you know it when you see it—stories with one eye on the past, watching to see what strange effect might be exerted on the present. Often there’s a feeling of being haunted, even if strictly speaking there aren’t any ghosts around. And for me the fun thing about thrillers is that they keep you on the edge of your seat, trying to guess what will happen next. Put all that together, and you have the atmosphere of The Dark Between The Trees.

What drew you to writing in this specific genre? Do you have any tips or advice for authors who want to write a thriller?

Atmosphere is a big part of The Dark Between The Trees, and I understood right from the beginning the kind of atmosphere I wanted it to have. Genre was almost a means to an end—what’s the best way of approaching a story so that it feels from the inside like I want it to feel? So I would advise people to start with that: stories with the same basic structure can be very different from each other based on their atmosphere, so start with the atmosphere, and it it’s meant to be a thriller, that will become obvious pretty quickly.

Where did the inspiration for the story come from? Is it based on a specific historical event?

There is no specific event that the book is based on, but in 1643 when TDBTT is set, there was an explosion of supernatural stories around the British Isles. Ghostly battlefields in the sky, devilish strangers, and of course witches—Matthew Hopkins, the self-declared Witchfinder-General, started hunting down supposed witches in East Anglia in the spring of 1644. It was a perfect storm of widespread stress and uncertainty while people’s attitudes to religion were in flux, and the news that travelled round the country was often dubiously true at best. A lot of people’s beliefs about reality were affected by their own preconceptions and a patchwork of local knowledge, which feels very human to me, somehow, and is also a great jumping-off point for a story about several different perspectives on the same event.

Your story is written with a dual timeline and POVs. What do you think is the appeal to readers and the advantages to authors with writing a book this way?

My timelines alternate between the group of soldiers in the 1640s, and the group of historians in the twenty-first century who’ve gone to search for them. The big advantage of switching between the two groups is that it can highlight their similarities and differences: the choices they make, the conclusions they come to, and the ways they behave towards each other as their journeys progress. Does anyone come out of that comparison looking great? I don’t think so, but it’s fun to watch.

When writing a story, what is your best strategy with getting to know your characters? How do you keep track of them? Did you have a favourite character in your story?

I try to find something to relate to in all my characters and not to play favourites. There’s quite a big cast in TDBTT—five historians and (initially at least) a group of seventeen soldiers. I know far more than what’s on the page about all of them, but I think they are more interesting in combination than separately. Interpersonal dynamics are way more important to me than backstory.

What kind of research did you complete for the story? Did you get to do any interesting interviews? Make any special trips to the setting?

The British Civil Wars are a long-time interest of mine but, as with a lot of wars, most of the easily accessible information is about the people at the top—the kings, the generals, the leaders. Most of my research was reading about ordinary soldiers, and especially some of the first-hand accounts of soldiering. It was also a great excuse for a good long walk now and again.

Share something you learned while researching for this book that surprised you.

Share something you learned while researching for this book that surprised you.

I love this story, which I first came across in Diane Purkiss’s The English Civil War: A People’s History. We know that, at this time, roving groups of soldiers had a reputation for going into villages and stealing everything—whether they needed it or not, sometimes whether they could carry it or not. Three centuries later, scientists looking at the effects of starvation at the end of World War II discovered that prolonged starvation causes people to become hoarders—as in, it literally changes something in their brain chemistry. And that puts a whole different spin on these seventeenth century soldiers, right? Suddenly they’re not spiteful and petty. Suddenly they’re desperately hungry men who don’t know where their next meal is coming from, or the one after that, and it’s changed something structural in their brains. But before the 1940s, nobody knew about that, so their theories about what was happening were different. We’re all working with incomplete information and trying to make the best sense of it that we can. Every historian is doing that, and every single one of my characters, and every reader too. That’s fascinating to me, and it was really something I wanted to play with in this book.

What is the last great book you read?

The Cherry Robbers by Sarai Walker.

![]()