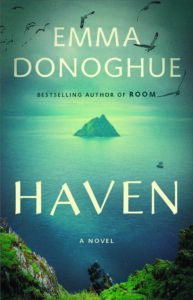

A Deceptively Simple Story: Confinement, Family and the Environment in Emma Donoghue’s Haven

WRITTEN BY MARGARET SKEA

Best known for her adult fiction, Emma Donoghue is a versatile and prolific author, whose fiction crosses many genres and for which she has won numerous awards. She has written for adults and children; fiction and non-fiction; contemporary and historical novels; and for stage, screen and radio; and moves, seemingly effortlessly, between them. So it was with anticipation of a very good read that I dived into a copy of her latest novel Haven. I wasn’t disappointed.

Best known for her adult fiction, Emma Donoghue is a versatile and prolific author, whose fiction crosses many genres and for which she has won numerous awards. She has written for adults and children; fiction and non-fiction; contemporary and historical novels; and for stage, screen and radio; and moves, seemingly effortlessly, between them. So it was with anticipation of a very good read that I dived into a copy of her latest novel Haven. I wasn’t disappointed.

Haven (Little, Brown; HarperAvenue; Picador UK, 2022) is set in Ireland in the 7th century and is a re-imagining of the first settlement of the Great Skellig – Skellig Michael – the larger of a pair of rocky outcrops off Ireland’s Atlantic coast. There is a tradition of monks on Skellig Michael from around this period, and though no details remain, archaeological evidence indicates they kept sheep, goats, and pigs and traded with the mainland for firewood, grain, and wine. The lack of documentary evidence of the first monastic settlement is a gift to an historical novelist, one which Donoghue exploits fully, choosing to present a purely fictional account distinctly different from that suggested by the archaeological record. She explained her rationale:

“Archeological evidence usually speaks of lasting patterns rather than brief ones – the report tells us about centuries of monks successfully herding and trading on the Skelligs. I wanted instead to imagine a first attempt, an interesting failure – how fast could things go wrong, as a lesson in how not to settle an island. The archeological report was extremely useful in telling me how rash and perverse it would have been to found an ultra-isolationist retreat without keeping those life-saving links to the rest of the world.”

For Donoghue, her fascination with the Skelligs began with a boat trip around the islands and, remarkably, she reports that the whole storyline – the three monks, the single summer and the final denouement – came to her all as a piece on that boat trip. The plot is very simple, but it is the richness of depth and colour in the characterization, and the depiction of the religious context, that make this an immersive read. Donoghue makes it clear that both her fascination with and much of her ability to enter so convincingly into the lives of these three 7th-century monks stems from her background and Catholic upbringing.

“I remain fascinated by all that’s beautiful to me in that heritage – the mysticism, the art, the music, the obsession with preserving and handing down Scripture, the sense of every tiny action of your day having some effect on the eternal destiny of your soul. But equally fascinated by the aspects of that tradition that appall me: the built-in misogyny and ascetic hostility to the body, authoritarianism, the emphasis on punishment and obedience.”

It is one thing to be fascinated by the religious “mindset”, another to be able to evoke it so compellingly. Many historical fiction writers say it is one of the hardest aspects of previous centuries to capture. For Donoghue, getting the “mindset” right is far more important than food or clothes and, aside from her deeply engrained knowledge of the Bible, stemming from her childhood, she read and re-read Scripture searching for appropriate quotations. Donoghue terms herself a “lapsed academic”, who thrives on having a lot of real historical and textual source material on which to base her fiction. Hence her rigorous research is unsurprising; what is more impressive is the way she seamlessly blends in the biblical quotations, the monastic prayers, and the stories of the saints, which form such a large proportion of the text, in order to enhance the story and develop the characters.

Several key themes struck me forcibly while reading Haven, including the impact of isolation and confinement. While Donoghue recognises that these themes have become leitmotifs of her work, for her it is less a matter of the theme itself than a practical matter of literary technique. She explains:

“Bringing the ‘walls’ in increases the emotional temperature between characters. And it makes my job as a world-builder so much easier if it’s a small world and I know every inch of it.”

Artt, the leader of the three monks, follows a religious principle way past the point of sanity, and the results of that idealistic obsession is a major driver of the plot. Donoghue highlights two other main themes – firstly the issue of the environment: “Because the monks are the first humans to land on the Great Skellig, their story is a kind of parable about what we do to the places we live.” Secondly, and importantly for Donoghue, the issue of family and parenthood. “Everything I’ve written over the last almost twenty years has mulled over the question of how to make a family with people who are in some ways alien to you.”

There are just three main characters in the novel, and although externally they are similar – identically dressed and having taken the same vows – they are very different individuals. It is clear from early on that Artt’s attempt to form them into a family unit will be fraught with difficulty.

The novel is structured in passages written from the alternating points of view of each of the three men. For Donoghue, choosing the point(s) of view is the most important decision she has to make before starting to write a novel:

“The teller makes the tale different. In the case of Haven, the plot actually grows out of the fact that these three uniformly dressed monks see things in such different ways, so switching between them made sense. I tried not to impose a fixed rhythm, but let each scene be narrated by the person who could tell it best.”

It is one of the novel’s strengths that by allowing the reader to view the situation from each of the characters’ differing perspectives, we gain both a close understanding of them and an appreciation of the mismatch between them and the potential difficulties that poses. There is an old monk, a young one and an idealistic dreamer, whose reputation for holiness has preceded him. Both Cormac and Trian have reasons to be especially susceptible to Artt’s invitation to join him. Cormac wrestles with a blending of the pagan beliefs of his childhood and his Christianity – a syncretism, common in the period, and in certain cultures even today, which Donoghue conveys perfectly in the statement: “Even though he’s been Christ’s man for a decade and a half, those ways still flow in him like an underground stream.” For Trian, there is a sense of not quite belonging. For both, Artt offers fulfillment in their calling.

Cormac and Trian are engaging characters with whom I found it easy to empathise, but I was unable to have any sympathy for Artt. Donoghue’s characterization of Artt was impacted by her extensive reading about cults and extremists and particularly about the ways in which a cult leader pulls in and retains their naïve recruits. She comments:

“Oh, he’s a monster, but I enjoyed writing roughly a third of the scenes from his point of view so that readers could understand that his actions aren’t randomly cruel but in line with his own zealous logic. I tried to make him quite attractive at the start, as cult leaders have to be. And I hope it comes across as poignant that this multitalented, energetic, ambitious dreamer, by following his ‘dream’ so inflexibly, effectively exiles himself to a rock in the ocean.”

Another major strength in Donoghue’s writing is her vivid description, and the use of pithy phrases, often with unusual combinations of words. Phrases such as “oxhides puzzled together over an ashwood frame” / “bearded with weed” / “small suns of coltsfoot” / “freshly curried with wool’s grease” / “people living like grubs in a log”/ “the sea forms a lumpy gruel”. It is interesting to note Donoghue considers dialogue, not description, her favourite part of writing and she particularly enjoys choreographing a row. However, for Haven she recognized that it demanded vivid description and therefore worked hard on that aspect. Perhaps it is the mark of a great writer that they can excel even in those aspects of writing that don’t come most naturally to them.

The difficulties of covid meant that it was impossible for Donoghue to visit Skellig Michael. This could have made her job of conveying the setting more difficult. Donoghue, however, didn’t see it that way:

“It really made little difference. Luckily it’s a place from which many tourists have uploaded photos and vlogs. Also, when you visit a modern spot, you have to do a lot of research and imagining to subtract all the modern elements and feel the place as it might have been in the time of your story. So there’s no boat that could take me to Skellig Michael in the seventh century – only writing this book could do that.”

From the outset of the novel, the reader is caused to wonder how it might end. As the tension builds and difficulties mount, this question comes more and more to the fore. The final revelation, which leads to the denouement, is both unexpected and startling. For Donoghue there was never any question as to how the novel would end, from the moment she first conceived the story:

“I wanted what breaks up the little family to be an issue of purity – the impossibility of absolute purity. Artt assumes they have left everything potentially corrupting behind them on the mainland, but of course all travellers have their own baggage, and the ‘us’ of any community always contains a bit of ‘the other’ if you look closely enough.”

This is an appropriately profound commentary on this deceptively simple story, which is a worthy and highly recommended addition to Donoghue’s already extensive list.

About the contributor: Margaret Skea is a multi-award-winning author of historical novels and short stories, whose aim is to provide a ‘you are there’ reader experience wherever and whenever her stories are set. Katharina Deliverance / Katharina Fortitude are a fictionalised biography of Luther’s wife.

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 101 (August 2022)