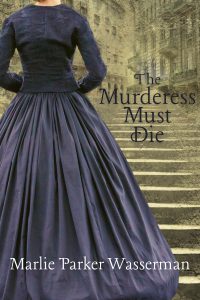

Launch: Marlie Parker Wasserman’s The Murderess Must Die

INTERVIEW BY SUSAN HIGGINBOTHAM

Marlie Parker Wasserman’s debut novel, The Murderess Must Die, tackles the challenging topic of the first woman to be executed in the electric chair at Sing Sing, New York State at the end of the 19th century.

What is your “elevator pitch”?

Martha Place—the first woman to be executed in the electric chair—is an unfamiliar name to most people, even those who can identify Mary Surratt and Ethel Rosenberg. But Martha became big news in Brooklyn in 1898, when she allegedly killed her stepdaughter, using poison, an axe, and a pillow.

What drew you to writing historical crime fiction?

What drew you to writing historical crime fiction?

Five years ago, I watched the History Channel while working out on a treadmill. One fact about Theodore Roosevelt stuck in my mind. When he visited Panama in 1906, he became the first president to leave the U.S. while in office. I decided to write a historical novel focused on that trip. As my story developed, I imagined various aspiring assassins on his trail. The resulting book will be my second novel, but it was the first I wrote. I had fun fitting what I call the puzzle pieces together, and so found my niche—historical crime fiction. I also found Martha Place’s story, because researching Roosevelt led me to his refusal to commute her sentence.

What attracted you to writing Martha’s story in particular?

The more I read about Martha, largely in newspapers, the less I knew about her. Some reporters considered her shrewd. Others, ignorant. Some called her attractive. Others, heinous. No one interviewed her and she had few friends. I needed to try to understand why a middle-class woman, who had not been in much trouble with the law previously, would lash out at her stepdaughter. My novel didn’t include much of a mystery since we know Martha is the likely murderess, so for me the mystery was the motivation. What led her to snap?

You took an unusual approach to this novel, telling Martha’s story from many perspectives. What made you choose this method?

As I researched Martha Place, I realized that her story—and her alleged crime—affected a wide circle of people. Her actions obviously changed the lives of her seven lawyers and her siblings. Her actions also changed the lives of people we generally don’t hear from, such as prison matrons and her executioner. Martha Place stood at the center of her own story, but that story radiated out. For example, if you had been the prison matron who served breakfast to a woman who walked down death row an hour later, wouldn’t you remember that? If I had to start my novel again, I would still employ the multiple points of view of several characters. Although I used chapter titles to alert readers to the shifts, some readers will still consider my approach “head hopping.” Multiple POVs are not for everyone.

Did your opinion of Martha change over the course of researching and writing your novel?

Yes. I became increasingly sympathetic to Martha. I shouldn’t say that since it is not politically correct to identify with the killer rather than the victim. Martha struck me as extremely lonely and frustrated that her life had turned out badly. On the other hand, I grew increasingly certain of Martha’s guilt. I started the novel unconvinced that she committed murder, but over time I had to conclude that she probably did the deed. Ninety-nine percent likely. As I wrote the novel, I did pay attention to the remaining 1%, because I believe there will always be a tiny bit of doubt.

You used court and other archival records in researching your novel. Did you have any difficulty in locating these old records?

Of my various writing projects, the story of Martha Place was by far the hardest to research. Her court proceedings seemed endless, and reporters gravitated toward labels that I knew were inaccurate. For instance, they used the words “indictment,” “arraignment,” and “grand jury” indiscriminately. I wrote dozens of letters to court officials, trying to find the records of preliminary hearings. If they existed, I could not find them. After four months of effort, I finally found the eighty-page transcript of the actual court trial. While I sought court records, I also researched Martha’s seven lawyers, trying to get a sense of their backgrounds, ages, and appearances. I found significant material on the better-known lawyers, and almost no material on the lesser-known ones. My general rule as I write historical fiction is to cling to the facts that I have learned, rather than reinventing history, but to feel free to fill in the gaps for what is unknown.

Did you visit any of the places associated with your novel?

Did you visit any of the places associated with your novel?

I wrote much of the novel during the early months of the pandemic, so I did not travel. I compensated by reading whatever I could find about Sing Sing, but that was difficult because the place was not static. Some buildings were demolished, others were constructed, and the histories of the place are imprecise about dates. Also, Martha was imprisoned in the old hospital building, not a main cellblock. Few observers wrote about the old hospital, which was in minimal use at the time. Another site on my mind was Martha’s gravesite. She was buried about fifteen miles from where I was living. Despite COVID, I could have safely visited such a deserted cemetery and neglected to do so. The one place I did visit was the New Brunswick, NJ home of her brother, Peter. That gave me a sense of distances and neighborhoods in a town Martha lived in for a number of years.

One of the more intriguing minor characters is the “prison angel” who ministers to Martha. Was she a real person, or based on one?

Emilie Meury is a historic figure, who truly did minister to Martha before and after her conviction. I did substantial research on Emilie and wish I could have used more of my findings. She is fascinating in her own right, though I wanted her in the novel largely to depict Martha’s hunger for friends, and Martha’s manipulation of spirituality for her own purposes.

What is the last great book you read?

Colson Whitehead, Harlem Shuffle.

A review of The Murderess Must Die appears in issue 98 of Historical Novels Review.

![]()

HNS Sponsored Author Interviews are paid for by authors or their publishers. Interviews are commissioned by HNS.