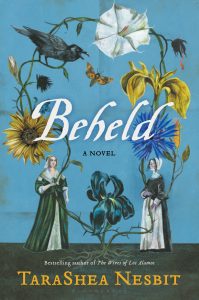

The Pilgrim Fathers Beheld

WRITTEN BY JENNY BARDEN

Beheld by TaraShea Nesbit (Bloomsbury, 2020) is remarkable, one of those rare novels that is both literary and accessible, thought-provoking and captivating, a delight to read and a wrench to put down. As an historical novel it is perfectly formed, immersing the reader convincingly in the mindset of those adventurous separatists who sailed to New Plymouth in the early seventeenth century. The twist to this retelling of a familiar tale is that it reveals the voices of the travelers accompanying those we now know as the “Pilgrim Fathers”: the women and Anglican servants upon whom they depended for their survival yet who cannot be heard in the records left behind. “I am drawn into America’s past,” says Nesbit, “and I am urged forward to speak into the gaps, particularly where powerful narrators (often white men) have occluded the voices of others.”

Beheld by TaraShea Nesbit (Bloomsbury, 2020) is remarkable, one of those rare novels that is both literary and accessible, thought-provoking and captivating, a delight to read and a wrench to put down. As an historical novel it is perfectly formed, immersing the reader convincingly in the mindset of those adventurous separatists who sailed to New Plymouth in the early seventeenth century. The twist to this retelling of a familiar tale is that it reveals the voices of the travelers accompanying those we now know as the “Pilgrim Fathers”: the women and Anglican servants upon whom they depended for their survival yet who cannot be heard in the records left behind. “I am drawn into America’s past,” says Nesbit, “and I am urged forward to speak into the gaps, particularly where powerful narrators (often white men) have occluded the voices of others.”

In the process of this listening into the silence of history Nesbit offers us new insights that are challenging and disturbing, we see avarice and division where history lessons once presented a noble quest for freedom, the “oppressed” Puritans become the oppressors treating their Anglican companions as outsiders, women are abused and exploited, particularly those of lower class, and indigenous people are slain on a pretext. Throughout much of the book there is an ominous ramping up of tension leading to the murder of the first colonist signposted on the very first page, and there is the dark cloud of likely suicide – a possible answer to the mystery which was Nesbit’s inspiration: why William Bradford, the first Governor “would not mention the cause of death of his first wife, Dorothy, in his account of the founding of Plymouth.” Dorothy may have slipped from the deck of the Mayflower as another man later wrote, but for Nesbit: “That seemed suspicious. I had a sense Bradford was, if not lying outright, doing so by omission, leaving things unsaid with intention… I couldn’t get this watery ghost out of my mind. In some ways, I hoped by writing her she would leave me. But instead more women appeared.”

Dorothy’s voice surfaces only briefly, very much like a ghost; most often we hear Dorothy’s closest friend Alice, the Governor’s second wife, and Eleanor Billington, wife of John, an indentured servant from across the class and religious divide. Both speak powerfully in the first person. Nesbit has a knack of drilling down into the consciousness of a character, so the reader is right there in the moment, privy to that person’s innermost thoughts with all the vagaries of memory and conditioned reaction. How does she do this? “The best way to gather a consciousness around you is to live amongst it. My time machine was the original documents: court transcripts, letters to investors, business folk and friends, and Bradford’s book Of Plymouth Plantation. Initially, I moved through the intellectual endeavor of mindset – trying to understand the set of beliefs cohabiting at the time.” But to fully accomplish this, Nesbit says, she had to loosen her hold on the verifiable. “I felt ready to write the book when I’d started to see the fissures in the ‘facts’ – when Bradford’s book would say one thing, and a letter back to London would offer a conflicting account. Once the facts started to breakdown and appear instead as subjective bits, I then felt confident enough to get to writing freely.”

There are strong third person voices too. We hear John Billington and the later arrival “Newcomen”, and we eavesdrop upon the voice of a servant girl while she is being raped. Interspersed with these are vignettes such as the diary entry of Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop, who notes a hanging with as much dispassion and brevity as the death of a cow. Collectively this interweaving conveys the story in a way that is both profound and moving.

All the voices are convincingly true to period without being stilted or unfathomable. What techniques did Nesbit use to achieve this? “At some point, I heard something like blank verse in most of the seventeenth-century texts, and wrote with that in mind. When a sentence I was writing felt ‘off’, I’d put it in unrhymed iambic pentameter. That gave it a formalness and restraint that I imagined for Alice. For Eleanor, whose family was described by William Bradford as one of the most profane he’d ever met, I felt freed-up and knew I could disrupt the formalness by varying the rhythm.”

This concentration upon voice which somehow removes the narrator from the reader’s perception is accomplished with singular flair. Nesbit did something similar in her first book, The Wives of Los Alamos (Bloomsbury, 2014), written, unusually, in first person plural throughout. In that book, she says: “I was haunted by the decision to build atomic bombs, detonate them over civilians, and then leave a mess of radioactive waste for future generations to deal with.” No surprise that it was the lost voices of the women who were the focus there.

In Beheld the story is anchored in place as well as time. Nesbit reveals that she was “lit up” on seeing a map of Plymouth settlement. “Once I learned that the Billington family had their home at the crossroads, directly across from Bradford’s home, a lot of narrative possibilities opened up.” For all the promise of space presented by the New World, Nesbit shows us a colony under threat from outside and within, its inhabitants soon squabbling over small parcels of land, seizing the territory of the Wampanoag without compunction, and proudly displaying the severed head of a native leader above the meeting house.

Beheld opens our eyes to an early America that was ugly and savage, but we see beauty there too: the beauty of love and enduring friendship, of nature and renewal – of life. “I try not to ask too many questions about why particular subjects, people and themes move me to write,” says Nesbit, “for I fear, if I understand fully, the breathing will cease.”

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR: Jenny Barden is the author of The Lost Duchess, which focuses on the first attempt to found a permanent English settlement in North America. https://jennybarden.com

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 91 (February 2020)