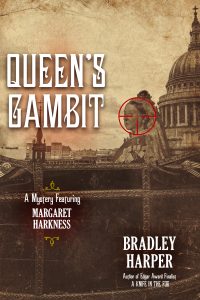

Is it time to feminise Sherlock Holmes? Queen’s Gambit by Bradley Harper

There have been many takes on Sherlock Holmes, the Great Detective, since Conan Doyle invented him in 1887. What they mostly have in common is the idea (central to the mythos) of a cold calculating machine. The latest example of this is Benedict Cumberbatch’s wonderful performance in the ITV series. But is this an out-of-date, vaguely misogynistic approach? Is it time to feminise Sherlock Holmes?

There have been many takes on Sherlock Holmes, the Great Detective, since Conan Doyle invented him in 1887. What they mostly have in common is the idea (central to the mythos) of a cold calculating machine. The latest example of this is Benedict Cumberbatch’s wonderful performance in the ITV series. But is this an out-of-date, vaguely misogynistic approach? Is it time to feminise Sherlock Holmes?

Author Bradley Harper, whose latest book is Queen’s Gambit (Seventh Street Books, September 2019), thinks that perhaps it is. “Sherlock Holmes,” he says, “belongs to everyone who loves justice.”

There have been attempts to feminise Holmes in the past, most notably in Laurie R King’s Mary Russell stories. Russell enters Holmes’ life as his apprentice and eventually marries him. She can apply Holmes’ methods but maintains a more ‘human’ approach than her mentor (although King’s Holmes is a much gentler character than Conan Doyle’s).

In Queen’s Gambit, Harper brings back Margaret Harkness, the latest female detective to join the canon, who he also featured in an earlier book (A Knife in the Fog). Margaret is based on a real person, although there is no evidence that the historical Margaret Harkness ever detected anything. She was a writer and journalist and, more importantly for the story, an early feminist.

Harper’s Margaret sees no reason why her gender should stop her playing the part of detective. When the social norms of the time (she’s a contemporary of the “real” Sherlock Holmes) mean that it is impossible for a woman to investigate as she would wish, she is not above adopting a disguise as a man. Despite this, Margaret is definitely a woman. Indeed, in Queen’s Gambit, her second outing, she falls in love and decides to take on the role of stepmother to another female would-be detective.

Harper is clear that Harkness is not a female Sherlock Holmes. Indeed, the story also features Professor Bell, the man Conan Doyle is supposed to have based Holmes on. Harkness has learned from Bell and we see her applying his techniques in the story, but she is not Bell. As Bradley Harper explains, “She is a female Holmes who is constrained by the society she finds herself in, but she has a unique perspective that deepens her powers of observation in interpersonal relationships and how power is wielded by those who have it.”

In this story, the constraints she faces mean that she has little opportunity to demonstrate her deductive skills. Indeed, when she does find an enormously important clue in an overheard conversation she fails to recognise its significance. Her failure to do so results in tragedy. In fact, she makes several blunders in the course of the story – demonstrating a human fallibility that Sherlock Holmes is apparently incapable of.

author Bradley Harper

Margaret Harkness is definitely not a godlike rational creature in the Sherlock Holmes mode but, arguably, someone more suited to what we want of our heroes (and heroines) today. She is kind and generous and brave. Holmes, of course, was all of these things too, but in Sherlock’s case the kindness and generosity were hidden most of the time, while for Harkness these are almost defining characteristics. Most importantly, Harkness (like the historical figure she is based on) is constantly battling to be allowed to do those things that a woman cannot generally do in Victorian times. Harper is consciously writing the story from a feminist perspective.

“A female Holmes, if written in the Victorian era, will have to find a way to function in a world where the cards are definitely stacked against her in a way that a male Holmes would not,” he says.

This is not to suggest that the book is in any way a political tract. Much of the feminism is implicit in the ‘voice’ of the character. Harper writes as an extremely convincing female, and puts this down to his understanding of the character, rather than to any conscious effort to write as a woman. He says, “What I think I do is write in the voice of a character whom I have thoroughly fleshed out in my mind and whose voice I can comfortably inhabit.”

The result is a far more convincing picture of the limitations that male society placed (and, by implication, can still place) on women than if the book were written either by an authorial voice calling for female equality or in the voice of an overtly crusading woman. (It’s interesting that the real Margaret Harkness never seems to have called herself a feminist.)

But, sexual politics aside, is Harkness a real successor to Holmes? I think not. Sherlock Holmes and those characters more or less modelled on him (like Ernest Dudley’s Doctor Morelle, Agatha Christie’s Poirot, or even Marvel Comics’ Batman in some of his guises) all represent rationality and external order imposed to restore normality after a murder (or occasionally some lesser crime). They are all outsiders. They will have some link with normal humanity – Holmes’ Watson, Morelle’s Miss Frayle, Poirot’s Captain Hastings – but they live isolated lives and are socially uncomfortable, if not completely inept.

Harkness, by contrast, has friends and easily forms new relationships. She even contemplates falling in love. She is grounded in the world she inhabits in a way that Sherlock Holmes (despite his much-suppressed feelings for Irene Adler) will never be.

Bradley Harper is conscious that this is not how the Sherlock Holmes character ‘ought’ to behave. He writes of how he has tried to ‘humanise’ Professor Bell too, saying, “I enjoy overturning the stereotype of an analytical robot-detective into a human being who is a compassionate champion of justice.”

In the case of Margaret Harkness this makes her a more interesting character and means that Queen’s Gambit is a more solid work than most of the Sherlock Holmes stories. (Almost all Holmes’ adventures are short stories, reflecting the fact that the tales are strong on plot but just don’t have the depth of characterisation necessary to carry a novel.) A female Sherlock Holmes may well be possible, but Harkness is not the Great Detective – and Queen’s Gambit is a much better book as a result.

About the contributor: Tom Williams writes thrillers about James Burke, a spy in the Napoleonic Wars, and rather heavier books about Victorian colonialism. He blogs on 19th-century history and other random stuff (mainly Argentine tango).