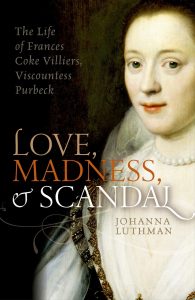

On the Periphery of Power: Love, Madness, and Scandal – the Life of Frances Coke Villiers, Vicountess Purbeck by Johanna Luthman

KATE BRAITHWAITE

Frances Coke was born in 1602, the last full year of the reign of Elizabeth I. She was the daughter of a prominent lawyer, Sir Edward Coke, and Lady Hatton, a granddaughter of Queen Elizabeth’s close advisor William Cecil. When she was fifteen, Frances made an appropriately aristocratic match with Sir John Villiers, brother of King James I’s favourite George, the Duke of Buckingham, but the marriage was unhappy. John suffered from bouts of mental illness and Frances turned for love to Sir Robert Howard, with whom she had a lengthy affair – and a son, also called Robert. The highly public scandal that surrounded their liaison is the principal subject of Johanna Luthman’s biography of this lesser known Stuart woman.

Frances Coke was born in 1602, the last full year of the reign of Elizabeth I. She was the daughter of a prominent lawyer, Sir Edward Coke, and Lady Hatton, a granddaughter of Queen Elizabeth’s close advisor William Cecil. When she was fifteen, Frances made an appropriately aristocratic match with Sir John Villiers, brother of King James I’s favourite George, the Duke of Buckingham, but the marriage was unhappy. John suffered from bouts of mental illness and Frances turned for love to Sir Robert Howard, with whom she had a lengthy affair – and a son, also called Robert. The highly public scandal that surrounded their liaison is the principal subject of Johanna Luthman’s biography of this lesser known Stuart woman.

Luthman first encountered Francis Coke Villiers while researching a previous work, “Love, Lust and License in Early Modern England: Illicit Sex and the Nobility (Ashgate, 2008). She was fascinated by Frances at once, intrigued by “the sheer human drama surrounding her at every turn” but she did not immediately see Frances as a candidate for her own biography because there were so few sources written by Frances herself. That changed, however, when Luthman came across Caroline Murphy’s Murder of a Medici Princess about Isabella de Medici. Murphy had achieved what Luthman aspired to do – bring a figure from the past to life despite a dearth of sources directly produced by the subject.

Unable to rely on Frances’ own words, instead Luthman worked extensively with State Papers, which she describes as “the rather eclectic mix of sources” and includes letters, orders, copies of interrogations, petitions and more. Because Frances was at the centre of a very public scandal – she petitioned the House of Lords twice and her lover Robert Howard was a Member of Parliament – the House of Commons debated Howard’s parliamentary privilege when he was tried for adultery. The published proceedings of Parliament and parliamentary journals were therefore also important sources.

But primary material from the early 1600s can be difficult to use, even though electronic access to scanned documents has transformed the research landscape in recent years. Luthman describes the greatest challenge to a historian of this period as the time and effort it takes to read and decipher these old documents. Seventeenth century handwriting is not easy to follow and standardized spelling and grammar rules were still a thing of the future. The physical documents can also provide their own challenges. The records of Chancery, for example, that Luthman accessed at the National Archive in Kew in London, “were the size of the whole table, and entirely filled with tiny text.”

author photo by Salai Sayasean

Even a fact as simple as Frances’ birth date was not easy to find – in this case, due to human error. Lutham explains, “The transcriber for the calendar of parish records had misread the name: therefore it did not show up in searches at all. It was not until I went through page after page of photographed and digitized manuscript records that I finally found the entry for “Frances Cook, doughter of Mr Cook the Quenes Maygesties Atorney general.”

With her research complete, Luthman was then able to grapple with Frances’ life and all of its ‘stranger than fiction’ realities. Disguises, cross-dressing and a high-speed coach chase through London are just a part of her story. Although Frances was not a major historical figure, Luthman believes that historians can make a valuable contribution to our understanding of a period by recovering the lives of those on the periphery of power and influence.

In a recent Reith lecture, renowned historical novelist, Hilary Mantel, cautioned that some of her fellow fiction writers were guilty of retrospectively ‘empowering’ women from the past. I asked Johanna Luthman how she felt about that, given Frances’ strong and independent character, as well as Frances’ mother Lady Hatton, who was also a force to be reckoned with. Largely agreeing with Mantel that “one should avoid judging historical subjects based on current ideals,” she also makes the point that while “women were limited in many ways … that does not also mean that they were entirely powerless…While women held few official positions (with the exception of court appointments to serve royal women), they could still wield significant power.”

Power, in Frances’ hands, is her ability and willingness to persist, to demand fairness, evade punishment and insist on her innocence, even in the face of enormous evidence of her adultery.

About the contributor: Kate Braithwaite is the author of Charlatan, a story of poison and intrigue in 17th century Paris.