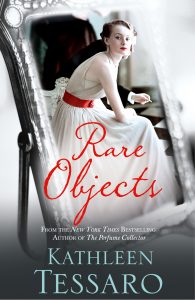

Privilege & Poverty: Kathleen Tessaro Explores the Darkest Secrets of Depression-era Boston

Kathleen Tessaro

My novel, Rare Objects (HarperCollins, 2016), examines the ways in which two young women struggle to make peace with their complex identities during the years of the Great Depression. “The land of opportunity” captures the romantic notion of the elusive American Dream, but for the characters in the book, especially Maeve Fanning, the social and economic divides of Boston in 1932 remain almost insurmountable. Raised in Boston’s North End, a ghetto of poor Italian immigrants, Maeve is no stranger to poverty, hardship and prejudice in a city whose social hierarchy was presided over by the distinctive Boston Brahmans. Maeve also harbors a shameful secret – she’s been institutionalized for alcoholism. In the mental hospital, Maeve met another young woman at the peak of Boston society, who’s being treated as mentally defective because of her sexuality. They become true friends, bound together by their vulnerabilities as they navigate the world outside the institution and fulfill their own versions of the American Dream.

My novel, Rare Objects (HarperCollins, 2016), examines the ways in which two young women struggle to make peace with their complex identities during the years of the Great Depression. “The land of opportunity” captures the romantic notion of the elusive American Dream, but for the characters in the book, especially Maeve Fanning, the social and economic divides of Boston in 1932 remain almost insurmountable. Raised in Boston’s North End, a ghetto of poor Italian immigrants, Maeve is no stranger to poverty, hardship and prejudice in a city whose social hierarchy was presided over by the distinctive Boston Brahmans. Maeve also harbors a shameful secret – she’s been institutionalized for alcoholism. In the mental hospital, Maeve met another young woman at the peak of Boston society, who’s being treated as mentally defective because of her sexuality. They become true friends, bound together by their vulnerabilities as they navigate the world outside the institution and fulfill their own versions of the American Dream.

Alcoholism in America rose dramatically among women during the years of Prohibition. Ironically, Prohibition, along with the women’s right to vote, broke down the social barriers that once kept “respectable” women out of the traditionally male world of saloons and bars. With alcohol consumption forced underground, suddenly nothing was more glamorous or enticing than drinking. For the first time, women were welcomed into the same venues and served on equal terms with men. Heroines emerged in books and movies to advertise this new freedom – openly sexual creatures like Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, and Joan Crawford, all of whom epitomized hedonistic excess.

However, the stigma of depravity and defective morality still clung to alcoholism, especially for women. It was assumed that alcoholic women were inherently genetically inferior. In an era when eugenics was viewed by many as the key to America’s political and economic supremacy, some states even went so far as to sterilize female alcoholics. There was little or no conception of alcoholism or addiction as a disease. Instead, it was viewed as a disgusting personal failing – a symptom synonymous with the dissolution of the fabric of society caused by the influx of immigrants and their corrupting influences on white Anglo-Saxon Protestant America.

The mental institution featured in the novel is Binghamton State Hospital in New York, originally the New York State Inebriate Asylum. With its Gothic Revival architecture and extensive grounds, it once hosted wealthy private patients but was converted into a state mental hospital at the turn of the century. Most of the scenes in the book are taken from personal experiences of patients there or in similar institutions. State-of-the-art treatments included “hydrotherapy” — binding patients to a metal gurney and wrapping them in icy wet sheets for up to six hours at a time, or spraying them with freezing water from fire hoses. Although electric shock treatments weren’t in popular use until later in the 1930s, other experimental forms of shock therapy included large doses of insulin to induce convulsions. Another popular therapy, touted as a wonder cure for all forms of addiction and even bedwetting, was the Belladonna Cure created by Charles B. Townes. A mixture of the delirium belladonna, henbane (otherwise known as insane root), prickly ash, and castor oil, this tincture was administered every hour for 50 hours straight, resulting in severe vomiting, hallucinations and excessive diarrhea. It was aptly nicknamed “the puke and purge.”

It’s difficult to imagine that these therapies represented forward thinking in mental health treatment of the time. Yet in some ways we still struggle as women to confront our difficulties without trepidation and shame. And beneath the idolized slogans of America’s freedom and equality for all, darker prejudices and fears still threaten our capacity for acceptance and achievement.

About the contributor: Kathleen Tessaro was an early member of the Wimpole Street Writers. Previous novels include Elegance, Innocence, The Flirt, The Debutante, and The Perfume Collector. Kathleen lives in the USA with her family. kathleentessaro.com

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 77, August 2016