Mary Surratt: Conspirator or Victim?

by Susan Higginbotham

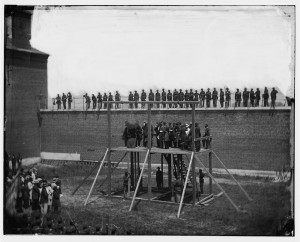

Mary Surratt awaits her execution (photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On July 7, 1865, a middle-aged, middle-class widow, unremarkable in appearance, stepped onto the gallows and plummeted to her death, becoming the first woman to be hanged by the United States government. But even though a military tribunal had judged Mary Surratt to be complicit in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, the debate about her guilt or innocence was only just beginning,

Mary’s march to the scaffold began in the fall of 1864 when, saddled with debt from her alcoholic husband, who had died two years before, she leased out the tavern she operated in Prince George’s County, Maryland and moved to Washington, D.C. Some years earlier, her husband had acquired a house there, and Mary decided to operate it as a boardinghouse. Two of her grown children, John and Anna, came to Washington with her; the third, Isaac, was serving in the Confederate army. John, too, served the Confederacy, but in a different way: making the dangerous trip across the Potomac River to carry clandestine messages from North to South.

For the rest of 1864, life went on in Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse no differently than it did in the many other small boardinghouses that dotted wartime Washington. Then, early in 1865, John Surratt brought home a new acquaintance: actor John Wilkes Booth. Soon Booth was stopping by the boardinghouse regularly. Sometimes he would sit in the parlor and converse with the ladies; other times he would confer with John Surratt privately. He visited even when John Surratt was away from home.

Around the same time Booth began frequenting the boardinghouse, a stream of odd guests began to appear, staying for only a few nights at a time. One man came twice, calling himself Mr. Wood on the first occasion and Mr. Payne on the second. Another, whose German surname no one could pronounce, was scruffy and disreputable looking. A lady guest kept her face shielded by a veil. One boarder, John Surratt’s school chum Louis Weichmann, began to wonder just what was going on — and he wondered even more when, one day in March, John Surratt, Booth, and Payne, agitated and waving weapons about, stormed into the room Weichmann shared with Surratt, then abruptly adjourned to the privacy of the attic.

In fact, the men were plotting the kidnapping of President Lincoln. Their scheme failed, but the next month, Booth changed history with a single Derringer shot at Ford’s Theater. At about the same time, just blocks away, a powerfully built man forced his way into the home of the Secretary of State, William Seward, who was recovering from a carriage accident, and attacked him in his bed.

Within hours of the assassination and the assault on Seward (who survived), police, tipped off that Booth had spent time at H Street, turned up at Mary Surratt’s boardinghouse. They searched the house but left after finding no sign of Booth or John Surratt, who was suspected of the assault on Seward. By the late evening of April 17, however, military authorities had acquired more evidence. They again came to the boardinghouse. This time, they took Mary and all those staying with her at the time into custody. As the party awaited transportation to Washington’s military headquarters, a man in grubby but well-made clothes turned up at the door with the unlikely excuse that he had come to dig a ditch for Mary the following morning. Asked to identify him, Mary swore she had never seen him before. In fact, she had seen him several times: he was the Mr. Payne who had stayed at her house just a month before. He was also, Seward’s servant soon confirmed, the man who had assaulted the Secretary of State.

By the time federal authorities caught and killed Booth in Virginia, Mary, Payne (whose real name was Lewis Powell), and six others had been identified as his co-conspirators. While the evidence against Powell was ironclad, the cases against some of his codefendants were weaker, and it was decided to try the eight before a military commission (which did not require a unanimous verdict to convict) instead of in a civilian court.

The trial began in May 1865. The chief witnesses against Mary were her former boarder, Lewis Weichmann, and the tenant at her Maryland tavern, John Lloyd. They testified to two particularly damning incidents: on April 11, three days before the assassination, Weichmann had driven Mary to her tavern, ostensibly for Mary to meet with a man who owed her money. On the way, they met Lloyd, to whom Mary gave a message: to have some “shooting irons” ready for a party who would soon call for them. Worse, on the day of the assassination itself, Mary had received a visit from Booth. Having heard that she was going to the tavern again, he had given her a package to hand to Lloyd, along with a message: have the guns ready, along with some whiskey, as they would be called for that very evening. Indeed, Booth and his companion, David Herold, did turn up at the tavern that evening and called for the guns and whiskey, as well as the package, which contained a field glass. Also weighing against Mary was her suspicious claim not to have recognized Powell, who had stayed at her own house.

Neither Lloyd nor Weichmann was an ideal witness, however. By all accounts, Lloyd was a heavy drinker who had been drunk when Mary saw him that fatal Good Friday, though how incapacitated he had been was debatable. Weichmann, though sober and steady, was also compromised. He had been close friends with John Surratt and had got on well with another defendant, George Atzerodt. One witness claimed that he had shared War Department records with John Surratt and his Confederate friends, and John Surratt later insisted that Weichmann had wanted to join the conspiracy but was disqualified because he could neither ride a horse nor shoot a gun. Some believed that had Weichmann not testified so freely against his landlady, he would have been on trial himself.

Under the law at the time, criminal defendants in most American courts were not allowed to take the stand, so Mary, who under interrogation had vehemently denied knowing anything of the assassination, delivering messages about shooting irons, or recognizing Powell, had to rely on impeaching Weichmann and Lloyd. For all of their shortcomings, both witnesses proved enough to convince a majority of the commissioners that Mary Surratt was guilty of conspiring to murder the President.

Was she guilty? A pious Catholic who would not have wanted to have gone to her death with a lie on her lips, Mary went to the gallows insisting on her innocence, and Lewis Powell, who was certainly in a good position to know, claimed that Mary had not been complicit in the assassination, although he acknowledged that she might have known that something untoward was going on. John P. Brophy, a young man who was friendly with the Surratt family and Weichmann, became convinced that the latter had been coerced into giving false testimony. Weichmann himself would spend the rest of his life justifying his trial testimony and rather pathetically seeking praise for his actions. But Lloyd’s testimony was more damning than Weichmann’s, and it was corroborated by the undeniable fact that Booth had indeed turned up at the tavern after the assassination to claim the weapons which Mary had allegedly told Lloyd to have ready. All in all, the evidence allows a case to be made by either the prosecution or the defense; indeed, the two most recent biographers of Mary, Elizabeth Steger Trindal and Kate Clifford Larson, reach diametrically opposed conclusions.

Unlike those writing nonfiction, novelists have the luxury of offering a definitive answer to the question of Mary’s culpability. The two twentieth-century novels in which Mary is the major character each come down on the side of Mary’s innocence, although the books are in all other respects quite different.

Helen Jones Campbell published The Case for Mary Surratt in 1943. Passionately convinced after extensive research that her subject was wrongfully convicted, Campbell put forth her thesis with such vigor that the book is sometimes treated as a work of nonfiction rather than a historical novel. Unfortunately, the polemical element in this novel overshadows the characterization. Passive and listless, Mary makes a splendid martyr, but not a compelling heroine.

In Pamela Redford Russell’s The Woman Who Loved John Wilkes Booth, published in 1978, Mary’s daughter, Annie, addicted to laudanum and all but sleepwalking through her dreary days, reluctantly accepts her mother’s diary from her former jailer, setting in motion a journey of self-discovery that will allow Annie to reconnect with those around her. Although Russell’s Mary, like Campbell’s, is innocent of any crime, The Woman Who Loved John Wilkes Booth (the title of which may mislead some readers into expecting steamy Boothian romance) is concerned not with exonerating Mary but in exploring the emotional lives of Mary and her daughter. As such, it makes for an engrossing, character-driven read.

The best-known fictional treatment of Mary, however, is cinematic: Robert Redford’s 2010 film The Conspirator. Starring Robin Wright as Mary and James McAvoy as her attorney, Frederick Aiken, the film is less concerned with her guilt or innocence than with the legality of the proceedings against her. The film takes a number of liberties in making its points, such as giving Mary several courtroom outbursts — but it is thought-provoking and well acted.

Two novels featuring Mary will be published in 2016. Jennifer Chiaverini’s Fates and Traitors: A Novel of John Wilkes Booth (Dutton, September), has Booth’s mother, sister Asia, sweetheart Lucy Lambert Hale, and Mary as its protagonists. My own novel, Hanging Mary, to be published in March, is narrated by Mary and by her young boarder, Nora Fitzpatrick. A century and a half after Mary’s execution, the question of what the widow knew — or didn’t know — continues to intrigue.

About the contributor: SUSAN HIGGINBOTHAM is the author of six historical novels, including the forthcoming Hanging Mary (Sourcebooks, 2016), her first novel to be set in the United States. She writes nonfiction as well and has contributed several articles to the Surratt Courier, a publication of the Surratt Society.

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 75, February 2016