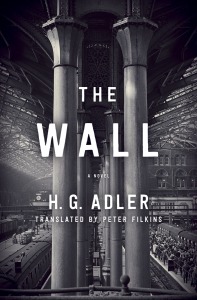

The Wall by H.G. Adler Now Available in English

EDWARD JAMES

H.G. Adler’s The Wall is subtitled A Novel, but this is a novel like few others. It has been compared to Joyce’s Ulysses and indeed is written as a stream of consciousness. There are no chapter breaks, despite its length, and no breaks to indicate shifts of time and place, which are frequent and sudden. There are paragraphs (the book is not that Modernist) but they can be extremely long and contain sentences that run for over 100 words. Unlike Ulysses it is not constrained by time and place but ranges over two decades and two countries in no chronological, geographical or other order. The “story” begins with the narrator looking out of the window of his study and ends in the same way, presumably on the same day. In between we have a flight of memory, which slides between remembered incidents as one memory sparks another and occasionally slips into fantasy. In that sense the story is true to life, for that is how memory works before we cut and edit it, but it is hard work for the reader.

H.G. Adler’s The Wall is subtitled A Novel, but this is a novel like few others. It has been compared to Joyce’s Ulysses and indeed is written as a stream of consciousness. There are no chapter breaks, despite its length, and no breaks to indicate shifts of time and place, which are frequent and sudden. There are paragraphs (the book is not that Modernist) but they can be extremely long and contain sentences that run for over 100 words. Unlike Ulysses it is not constrained by time and place but ranges over two decades and two countries in no chronological, geographical or other order. The “story” begins with the narrator looking out of the window of his study and ends in the same way, presumably on the same day. In between we have a flight of memory, which slides between remembered incidents as one memory sparks another and occasionally slips into fantasy. In that sense the story is true to life, for that is how memory works before we cut and edit it, but it is hard work for the reader.

To make things easier, the translator, Peter Filkins (the book was originally published in German in Austria in 1989, the year after the author’s death, and is the concluding volume of a trilogy) has added a lengthy introduction at the beginning and a list of characters and a “Summary of Events” at the end, cross-referenced in detail to the pages in the book. In the introduction, Filkins explains that the work is not autobiographical, although written in the first person, since the narrator has a different name to the author, his wife has a different name, and they have a different number of children. However it is clearly a thinly fictionalised autobiography, and Filkins admits that the anonymous locations in which most of the book is set are Prague and London, where Adler lived.

The book is classified on the flyleaf as “Holocaust – survivors fiction”. I have not read the earlier volumes of the trilogy, which presumably cover the narrator’s experiences during the war. The Wall deals with the 10 to 15 years after his release from an unnamed camp, presumably Auschwitz, and his struggle to adapt to post-war life. Other reviewers have called this a study in survivor guilt, but if so the narrator’s guilt is deeply buried. His chief emotion is bitterness against his friends and neighbours who avoided deportation, either by escaping to the west before the war or evading it during the Nazi occupation. He feels that they do not understand what he suffered and that their offers of friendship and help are hypocritical. It is clear to the reader that it is they who have the guilt feelings; they feel they ought to help, but they find him a nuisance and are exasperated by his apparent reluctance to help himself. The reader himself has guilt feelings; he feels he should struggle through to the end because the author has suffered so unjustly, but it is not easy.

The narrator is not a sympathetic character, nor does he pretend to be. The closest parallel I know to this book is A Death in the Family by Karl Ove Knausgaard (Secker 2014). It is written in the same style, and is similarly autobiographical and candid. I belonged to a book group which read this and they all hated it because they did not like the narrator. I think many people will dislike The Wall, but enough will admire it to make it sell like Knausgaard’s work.

Since this a novel unlike most others, the best way to read it is not to approach it like other novels. There is no narrative thread, so dive in anywhere and, as they say, enjoy! Use the Summary of Events as a guide. Some of the pieces are wonderfully entertaining, such as the encounters with embarrassed friends trying to escape the narrator without being offensive or lyrical episodes in the Sudeten mountains or grim life in austerity Britain in the winter of 1947. Do not be worried if it does not make sense. Accept the fantasies as well as the realism, enjoy them equally, and do not feel you have to press on to the end, for there is no denouement.

Finally, is there a message? The Wall is not about survivor guilt or post-traumatic stress, it is about alienation. It is about a man who is snatched from the world and when he returns it has all changed. Everything and everyone he knew has gone and he has no place in the new order that does not value his skills or experience. It is similar to the “novels of return” of the 1920s, about soldiers coming back from the Front. And what is the answer? Adler’s hero is lucky enough to find the love of a good and very patient woman.

About the contributor: Edward James is a Reviews Editor for the Historical Novels Review and has recently published Freedom’s Pilgrim: A Tudor Odyssey on Amazon and Smashwords. He plans to publish a further historical novel, The Frozen Dream in the near future.