Art in Historical Fiction Interview Series featuring Alana White

Stephanie Renee dos Santos

Welcome to week five of our series. It’s my pleasure to introduce Alana White, author of The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, a historical mystery with a weeping painting at the center of the intrigue. In 1480, a Florentine lawyer, Guid’Antonio Vespucci, must solve a murder mystery with the help of his nephew, Amerigo, to save Florence from warring factions, the Pope, and possibly another Turkish attack. Guid’Antonio and Amerigo investigate lovers’ stories, search the nooks and crannies of Florence, through churches, bars, and the artist workshop of Sandro Botticelli. They are seeking a missing monk who may hold the answers to the mysteries. Filled with poetic prose, White’s novel sweeps us through the cobblestone alleyways, political loyalties, vibrancies, and violence of Florence during the Italian Renaissance.

Welcome to week five of our series. It’s my pleasure to introduce Alana White, author of The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, a historical mystery with a weeping painting at the center of the intrigue. In 1480, a Florentine lawyer, Guid’Antonio Vespucci, must solve a murder mystery with the help of his nephew, Amerigo, to save Florence from warring factions, the Pope, and possibly another Turkish attack. Guid’Antonio and Amerigo investigate lovers’ stories, search the nooks and crannies of Florence, through churches, bars, and the artist workshop of Sandro Botticelli. They are seeking a missing monk who may hold the answers to the mysteries. Filled with poetic prose, White’s novel sweeps us through the cobblestone alleyways, political loyalties, vibrancies, and violence of Florence during the Italian Renaissance.

Why is the painting crying?

Stephanie Renée dos Santos: At what point and how did you decide that an art component would be an integral part of your Italian Renaissance historical mystery?

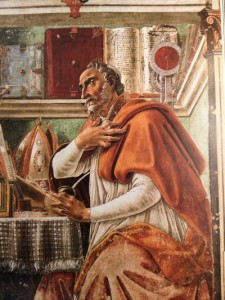

This is the “Saint Augustine” Sandro painted in the Vespucci family church in 1480. He is finishing it as the story opens, and a “clue” he paints into it leads to the resolution of the story. (The hidden note was discovered by restorers relatively recently.) The painting (fresco) remains in the church today: Ognissanti, or The Church of All Saints.

Alana White: My protagonist is real life 15th-century Florentine lawyer Guid’Antonio Vespucci, a well-known political figure and close friend of the unelected “prince of the city,” Lorenzo de’ Medici, when Florence experienced the most creative period in the city’s entire history. As I researched Guid’Antonio and his family, I learned they were close neighbors with Sandro Botticelli, who lived and worked around the corner from their palazzo. In fact, at the time of The Sign of the Weeping Virgin (August 1480), Sandro was completing the Saint Augustine for the Vespuccis in Ognissanti, or All Saints, Church. Digging deeper, I discovered Sandro added a short poem to the top of the fresco, where for centuries it remained hidden in the church shadows. Art restorers working in the church uncovered the poem in the relatively recent past. In The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, those few lines provide Guid’Antonio with the clue to solve the mystery at the heart of the story. Botticelli’s “Saint Augustine” remains in Ognissanti today (except when it is on tour).

SRDS: What compelled you to include and focus on art and artists of the time period and place in your historical novel?

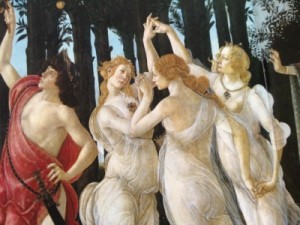

Sandro Botticelli’s “Primavera” plays a pivotal role in Weeping Virgin. The youth on the left is Giuliano de’ Medici, Lorenzo de’ Medici’s brother, who has been assassinated at the beginning of the story.

AW: The fact that the Vespuccis (as well as many other people in The Sign of the Weeping Virgin) are not only real people but also well-documented art patrons, too, gave me no choice but to include art in the story. The most popular workshop in town belonged to sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio (not Botticelli!). Verrocchio rented his house and work space from Guid’Antonio. Both Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci were Verrocchio’s apprentices. Leonardo drew a well-known sketch of Guid’Antonio’s kinsman, Amerigo (Vespucci) the Elder. These facts could not be ignored, (not that I wanted to ignore them). Guid’Antonio’s contemporaries—artists, poets, and politicians, alike—provided me with delicious connections to explore. These Renaissance marquee names were an inherent part of Guid’Antonio Vespucci’s daily life. To me, this is what made the Italian Renaissance glorious—all these people linked together. Needless to say, these are character-driven novels.

SRDS: What drew you to your specific visual art medium, the art work, and artist(s)?

AW: The people. The truth. Michelangelo is in the book, but only as a five-year-old in a scene with his father, who at the time was a successful government employee. Given Michelangelo’s age in 1480, I didn’t have to deal with him as an apprentice in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s famous school for sculptors. Frankly, I just thought it would be fun to include him as a boy in the marketplace with his father. I think the fact that all these people knew one another and worked with one another surprises and, I hope, entertains readers.

SRDS: How did you go about incorporating art and artists into the book?

AW: Sandro Botticelli’s fresco of “Saint Augustine” in the Vespucci family church provides the clue that solves the mystery. I also employed Botticelli to describe Guid’Antonio early in the book. As Weeping Virgin begins, we see Botticelli alone in the church applying finishing touches to the fresco. Eventually, two young monks run across the altar, and Botticelli watches them, eavesdropping on their conversation; then he paints his secret poem at the top of the fresco. Moments later, the same monks dart from the church and slam into Guid’Antonio and his nephew, Amerigo. Moments after that, we see Botticelli leave the church and step back to assess Guid’Antonio, who is now striding on down the street. I enjoyed describing Guid’Antonio through Botticelli’s eyes.

Another painting plays a key role in the story. This is the painting of the Virgin Mary that has begun weeping in the Vespucci family church. Florentines are interpreting the painting’s tears as a sign of God’s displeasure with Lorenzo de’ Medici (and by association, with Guid’Antonio) for the city’s recent war with the Pope. This, again, is an actual painting, the “Virgin Mary of Santa Maria Impruneta”. Already centuries old in 1480, the painting still resides in its home church in the small town of Impruneta near Florence.

SRDS: Do you have any message you were trying to convey by including art and artists in the novel?

AW: Only that these were—are!—real, flesh-and-blood people who happened to live in the same place at the same time, and who shared the same hopes, fears, dreams, and losses everyone does. By some miracle, Botticelli, Leonardo, and so many others were magnificently talented. The point, though, is that in the end, nothing really changes, and we are all basically the same. We are in this life together.

SRDS: What story lines do you see as unexplored in this niche of art in fiction?

AW: The Italian Renaissance is thick with untold stories. I find nuggets everywhere in my research. Extraordinary paintings like Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa” have led extraordinary lives. I have found a lot of possibilities in nonfiction works like the marvelous Pulitzer Prize winner, The Swerve (Stephen Greenblatt) and Brunelleschi’s Dome (Ross King). Research provides writers with terrific ideas for short stories and subplots, as well as for entire novels.

SRDS: What do you think readers can gain by reading stories with art tie-ins?

AW: I believe stories add emotion to the artwork itself. They add breath and life. Of course, the best nonfiction accomplishes this, too. Still—fiction infuses art with blood and bone.

SRDS: Why does fiction with art and artists matter?

AW: Such fiction explores artists as human beings with the same problems and victories we all experience. It enters the lives of women and men who knew sorrow and pain as well as success (we hope). It helps us hold our heads high through the good times and the bad.

SRDS: Are you working on a new historical novel with an art and artists thread? If so, please tell us a bit about the upcoming book.

AW: I am working on the prequel to The Sign of the Weeping Virgin. The story is set seven years earlier, in 1473. And yes, art plays a narrative role. In this case, it is Leonardo da Vinci’s early sketch, “Saint Mary of the Snows”. The sketch doesn’t provide a clue to a mystery but serves more as an “arc” for the story. As this work-in-progress opens, Leonardo, who is only 21 at the time, is just beginning the sketch; midway through the book, Guid’Antonio talks about the drawing with Leonardo. Then, at the end of the story, we see Leonardo has completed it. In his characteristic mirror-writing, Leonardo not only named but also dated the sketch: “Day of August 5, 1473.” About the sketch, he said, “I am content.” These three mentions draw a thread through the story.

SRDS: Any further thoughts on art in fiction you’d like to share or expand on?

AW: Only that no matter what period interests readers and writers most, it is sure to be rich with artists, their art, and their fascinating, often interrelated lives.

About the author: Alana White’s fascination with the Italian Renaissance led to her first short historical mystery fiction, then to the full-length novel, The Sign of the Weeping Virgin (Five Star, January 2013). Alana’s book reviews appear regularly in the Historical Novels Review. A member of the Historical Novel Society, Sisters in Crime, Mystery Writers of America, and the Author’s Guild, she resides in Nashville, Tennessee, where she is currently writing her second Guid’Antonio Vespucci mystery, a prequel to The Sign of the Weeping Virgin.

About the author: Alana White’s fascination with the Italian Renaissance led to her first short historical mystery fiction, then to the full-length novel, The Sign of the Weeping Virgin (Five Star, January 2013). Alana’s book reviews appear regularly in the Historical Novels Review. A member of the Historical Novel Society, Sisters in Crime, Mystery Writers of America, and the Author’s Guild, she resides in Nashville, Tennessee, where she is currently writing her second Guid’Antonio Vespucci mystery, a prequel to The Sign of the Weeping Virgin.

For more information about Alana’s work: www.alanawhite.com Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/authoralanawhite?ref=hl

Join us next Saturday July 5th for an interview with Maryanne O’Hara, author of Cascade

Interview posting schedule: May 31st Susan Vreeland, June 7th Mary F. Burns, June 14th Michael Dean, June 21st Donna Morin Russo, June 28th Alana White, July 5th Maryanne O’Hara, July 12th Stephanie Cowell, July 19th Cathy Marie Buchanan, July 26th Alicia Foster

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing & yoga workshops. She writes features for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first art-related historical novel, CUT FROM THE EARTH, a story of Portuguese tile and its surprising makers – The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 — and the wisdom of nature to guide and heal. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com & Join Facebook group “Love of Art in Fiction”

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing & yoga workshops. She writes features for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first art-related historical novel, CUT FROM THE EARTH, a story of Portuguese tile and its surprising makers – The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 — and the wisdom of nature to guide and heal. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com & Join Facebook group “Love of Art in Fiction”