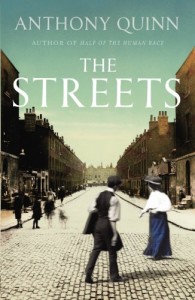

WSP Masterclass Series 2013: 3: Anthony Quinn on ‘astonishing disparities’

Richard Lee, Helen Boyd, Kate Braithwaite

The Walter Scott Prize shortlisted authors are at the pinnacle of contemporary literary historical fiction. We have asked each of them how they approach language in their writing. The resulting series of articles is a masterclass for aspiring writers and critics of this form of the novel.

HNS: In what ways do you use language to make your stories authentic to period and place whilst still engaging the modern reader?

HNS: In what ways do you use language to make your stories authentic to period and place whilst still engaging the modern reader?

AQ: For The Streets I did a fair bit of research into the street slang of the late Victorian era (the story is set in 1882) especially that concerned with trade and the lower circles of criminality. Much of the coster back slang (pot o’ reeb, yenep, etc) I picked up from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and The London Poor. The rest I gathered from Partridge’s Dictionary of Historical Slang.

HNS: With dialogue, what research or inspiration enables you to ‘make the dead speak’?

AQ: I don’t regard them as “dead”. When I’m writing about a set of people, whether they are suffragettes in 1911 or journalists and costers in the 1880s those characters are as real to me as my own friends – possibly more real, since I spend far more time in their company. Obviously you have to do the research as well, what clothes they wear, what they eat, how they speak, but quite often the character comes alive to me because of timeless things, like the colour of someone’s eyes, or a personal tic. Even the way a person walks.

HNS: How do you ensure your characters appeal to modern readers when humour, beliefs and attitudes may be very different today?

AQ: You can’t ensure it, you just have to write the characters you want to spend time with, whether they are good-natured, or mean-spirited, or a flawed mixture of the two. The word everyone uses these days is “relevant”, as though the only reason for reading historical fiction is to see ourselves reflected in its surfaces. That’s an awfully reductive way of approaching it. And the traffic is always one-way: instead of asking “Why is this book relevant to me?” we might just as well ask, “Am I relevant to this book?” It’s not wildly out of the question that many novels are more complex and intelligent than the people who read them. Books may demand things that readers just aren’t up to supplying. Readers are transitory creatures; books have a longer span in mind.

HNS: What sorts of emotions or reactions do you consciously leave unguided for the reader?

AQ: You leave as much as you dare to the reader’s imagination. As a reader I will always be on the side of the writer who lets me make the connection and draw the conclusion for myself. It’s a kind of compliment the writer pays to his readership not to fill in every blank.

HNS: What drew you to this particular story, this particular time?

AQ: I have a deep and abiding interest in the late Victorians, and particularly the astonishing disparities of London life – the gap between rich and poor then is almost inconceivable to us now. I read Henry Mayhew, whose period is a couple of decades before my story, though it gave me the basis of how a man might research the lives of the poor and destitute. The other major influence in my reading life has been George Gissing, the last great Victorian novelist, and I had his humane example always before me.

HNS: What other historical novelists do you read and enjoy?

AQ: Two contemporary writers I admire above all others. For the ingenuity of her plots it’s Sarah Waters; I recall a late night on holiday in Italy when I was halfway through her brilliant Affinity. I literally couldn’t go to sleep before I finished it. For the wit and elegance of his prose it’s Alan Hollinghurst. Having read and re-read all five of his books I feel in awe of his mastery. For me, The Stranger’s Child is one of the great novels of our time.

Catch up with the rest of our articles on the Walter Scott Prize 2013 here, or read our series on the WSP 2012 here, or follow the Borders Book Festival coverage of the award here.