Art in Historical Fiction Interview Series featuring Mary F. Burns

Stephanie Renee dos Santos

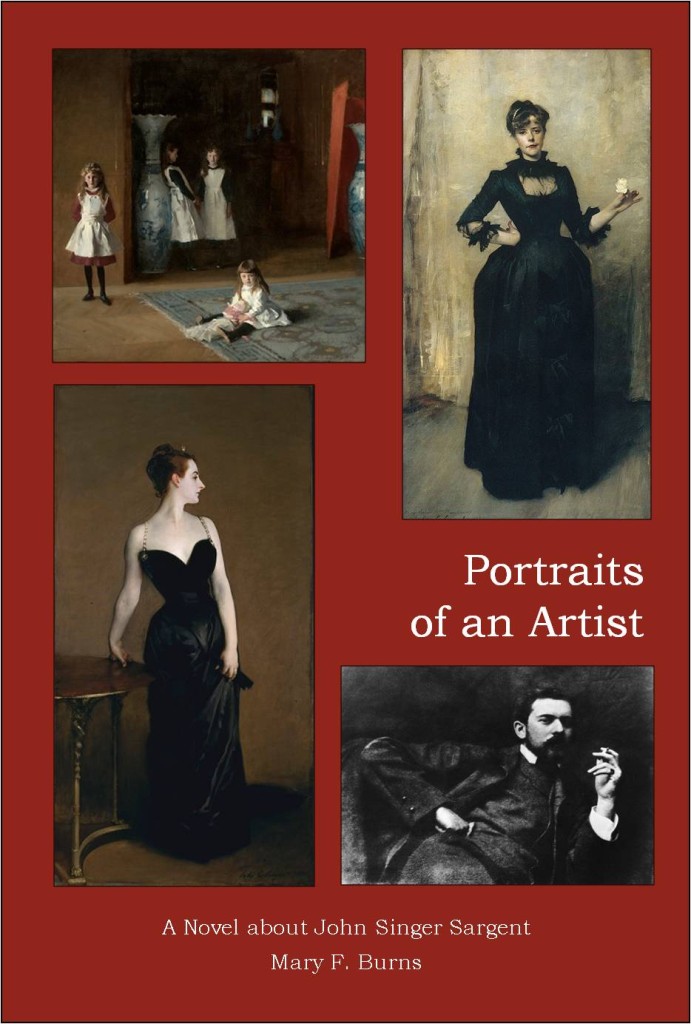

Welcome to the second Saturday of our series. It’s my pleasure to introduce Mary F. Burns, author of Portraits of An Artist. This is a historical novel about American portrait painter John Singer Sargent who worked in Paris in the 1880s, creating his greatest masterpieces: “The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” and the infamous “Madame X”. Both were dark psychological paintings that surprised and then shocked the local Parisian art scene, two paintings that changed the course of Sargent’s life in fabulous and then disastrous ways. The novel brings to life the voices of his paintings’ subjects, told incredibly from fifteen first-person points-of-view. Through his portrait sitters the prolific artist is revealed: his charisma, his secrets, his success, his ultimate struggle. With witty prose and insightful dialogue we are transported into the compelling and complicated world of the artist. Currently, Burns is working on a new historical time-slip mystery series featuring Sargent and his lifelong writer friend Violet Page. Read on for more insight into this upcoming project… Stephanie Renée dos Santos: Why did you choose your particular story structure to tell American portrait painter John Singer Sargent’s story in Portraits of An Artist? Will you please tell us about this choice? Mary F. Burns: My first draft of Portraits of an Artist, a historical novel about John Singer Sargent, was written in this style of third person object point-of-view. It was solid writing, I thought, but as my initial readers/advisors and I too came to see, it was, frankly, a little boring. The story unfolded in a straight, chronological line, there were a lot of characters who seemed to melt together, and there was a sort of relentless forward motion that was rather tiresome. So I re-wrote it. I briefly tried a first-person point-of-view with one of the major characters, Violet Paget, who was a long-time friend of Sargent’s, but then the book became all about her, which was not what I wanted. Then I wrote it with Sargent as narrator. His voice brought a great deal more vivacity and immediacy to the story, and I felt it was easier to care about Sargent and what he was going through—but he had to be in every scene! I couldn’t reveal what other people thought about him, or felt about him, and that—it became clear to me—was turning out to be the essence of my book: how to understand a mostly inscrutable, intensely private person who nonetheless was a huge success in the art world of the late 19th century. It wasn’t known, but it was rumored, that he was gay—or maybe not; that he had compromised a young woman of his acquaintance, and really should marry her—or maybe not; that he’d sold his soul (and body) for the chance to paint the most famous woman in Paris—or maybe not really…. What to do?

Welcome to the second Saturday of our series. It’s my pleasure to introduce Mary F. Burns, author of Portraits of An Artist. This is a historical novel about American portrait painter John Singer Sargent who worked in Paris in the 1880s, creating his greatest masterpieces: “The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” and the infamous “Madame X”. Both were dark psychological paintings that surprised and then shocked the local Parisian art scene, two paintings that changed the course of Sargent’s life in fabulous and then disastrous ways. The novel brings to life the voices of his paintings’ subjects, told incredibly from fifteen first-person points-of-view. Through his portrait sitters the prolific artist is revealed: his charisma, his secrets, his success, his ultimate struggle. With witty prose and insightful dialogue we are transported into the compelling and complicated world of the artist. Currently, Burns is working on a new historical time-slip mystery series featuring Sargent and his lifelong writer friend Violet Page. Read on for more insight into this upcoming project… Stephanie Renée dos Santos: Why did you choose your particular story structure to tell American portrait painter John Singer Sargent’s story in Portraits of An Artist? Will you please tell us about this choice? Mary F. Burns: My first draft of Portraits of an Artist, a historical novel about John Singer Sargent, was written in this style of third person object point-of-view. It was solid writing, I thought, but as my initial readers/advisors and I too came to see, it was, frankly, a little boring. The story unfolded in a straight, chronological line, there were a lot of characters who seemed to melt together, and there was a sort of relentless forward motion that was rather tiresome. So I re-wrote it. I briefly tried a first-person point-of-view with one of the major characters, Violet Paget, who was a long-time friend of Sargent’s, but then the book became all about her, which was not what I wanted. Then I wrote it with Sargent as narrator. His voice brought a great deal more vivacity and immediacy to the story, and I felt it was easier to care about Sargent and what he was going through—but he had to be in every scene! I couldn’t reveal what other people thought about him, or felt about him, and that—it became clear to me—was turning out to be the essence of my book: how to understand a mostly inscrutable, intensely private person who nonetheless was a huge success in the art world of the late 19th century. It wasn’t known, but it was rumored, that he was gay—or maybe not; that he had compromised a young woman of his acquaintance, and really should marry her—or maybe not; that he’d sold his soul (and body) for the chance to paint the most famous woman in Paris—or maybe not really…. What to do?

Having written the whole book from Sargent’s piont-of–view, though, was a very fruitful exercise, as I now felt I was thoroughly in his head—I had mapped his motivations, his feelings, his responses, so I really, really knew him. I pondered the notion of having multiple first-person voices, and then it hit me: the portraits would be the characters! They would tell the story of Sargent, from their points of view—each with his or her own voice—reliable or unreliable—vain, sincere, spiteful, honest, blinded by love or lust—and from those “portraits” of Sargent by his own “portraits”, the reader would be able to hear and understand the impact that Sargent had on all those people—lovers, friends, teachers, clients, judges—and infer some sense of who the man himself had been. And so I ended up with a novel that has fifteen first-person narrators, plus Sargent. Luckily, my publisher was as insistent as I was on using as illustrations a “headshot” of each of the portrait/characters at the beginning of the chapters in which they’re featured, along with their names. It was a challenge—but a wonderful one—to make each of their voices distinct, but I (humbly) think I met the challenge. I’ll leave it to my readers to decide. SRDS: What compelled you to include and focus on art and artists in your historical novel?

MFB: Seeing Sargent’s paintings for the first time, in 1999 at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., absolutely floored me. It was a special exhibition, the first in decades of major works by Sargent, and I went three times in three days. I was stunned by the size and glamour of the portraits, but even more by the uncanny psychological depths he managed to capture. You could almost see the women shivering from a case of “crispation de nerfs”, as Sargent’s friend Violet Paget referred to it, when she commented that his subjects were looking a little tense. The exhibit book that accompanied the show talked about how Sargent was asked to paint portraits of many of the ‘newly rich’ in England and Europe – industrialists and manufacturers who were making enormous fortunes throughout the 19th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, and who hoped to find a place in the upper class systems which were experiencing a good deal of flux. Sargent seemed to have picked up on the uncertainty and nervousness felt by these people on the rise, particularly the women, whose sumptuous gowns and glittering jewels couldn’t quite hide the fear of inadequacy and inelegance they might betray. A fantastic example of this is the portrait of “Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896). SRDS: What drew you to your specific visual art medium, art works, and artists?

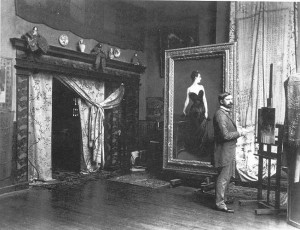

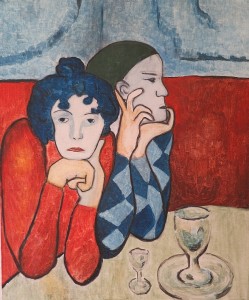

MFB: I have been a visual artist myself, mostly in college – watercolors, some oils, pen and ink—and then lately, I’ve been working in stained glass. I took a lot of art history courses in college, and when my husband and I travel, the art museums are the first places we visit in any city. Here are a couple of examples: a copy I made of Picasso’s “Absinthe Drinkers” (my mother’s comment at the time was “Oh, Mare, they look so sad!”) and my most recent stained glass project, “The Four Seasons”. SRDS: How did you go about incorporating art and artists into the book? MFB: After having read some novels about artists that put in a little too much detail about how they prepared canvasses, made the paint, used certain kinds of brushes, etc. (which I kept skipping over!), I decided to incorporate Sargent’s painting “process” in a way that would illuminate his character and approach to life – such as, he often took a running leap from across the room, dashing at his paintings with a brush heavy with paint, attacked the canvas, and then running back to see the effect – all while smoking a cigar or singing at the top of his voice. He often had visitors and relatives of the sitter in the studio, and he had people play the piano and sing to keep the sitter from getting bored. So I concentrated on these kinds of details rather than facts about the actual painting process. A fascinating point is that Sargent, a very tall man (over six feet), towered above his subjects, and many of his portraits reflect that perspective, as if the subjects are looking up at us, which often enhanced the feeling of uncertainty or nervousness. The other area I tried to present was his thinking and ruminating about how to pose a subject, what kind of props or costume should be used – he had a huge collection of draperies, clothing, vases, tables, chairs, etc., that he would take with him when he went to different cities so he would have access to his props when he needed them. He was very particular about the clothing that his subjects should wear, and would spend lots of time in the ladies’ wardrobes choosing dresses and jewelry. SRDS: Do you have any message you were trying to convey by including art and artists in the novel? MFB: Not consciously, I think, but when I think about how I feel as an artist (and a child of the 60s), I sympathized very strongly with a bohemian lifestyle in the midst of fairly rigid societal expectations, which Sargent and his contemporaries had to deal with. Fortunately for him, his mother in particular felt too constrained by the straight-laced society of East Coast America (Philadelphia and Boston in particular, where his family was from), and preferred the relative ease and sophisticated tolerance of European capitals where they frequently stayed – Rome, Florence, Siena, Venice, Paris, and London. Nonetheless, in mid- to late-Victorian times, one still had to watch one’s Ps and Qs, as it were, if one wanted to be acceptable to bourgeois society, which was where the money was for things like portraits. SRDS: What story lines do you see as unexplored in this niche of art in fiction?

MFB: Thanks for the caveat! I think one area which I might like to explore, and which I think hasn’t been gone into, is artists in the time of war, specifically WWI and WWII – connecting the upheaval in the world with the radical, sometimes violent, breaks with traditional art that started with the Impressionists (relatively “benign”) and went on to the fauvists, the expressionists, the abstract artists, and so forth. Sargent was engaged as a ‘front-line’ artist for the Allies in WWI, and has a very famous painting that has recently been on display in London, called “Gassed” (1918), very different from his usual work. He also painted “regulation” portraits of generals and other officers, about whom he made some pretty nasty comments in private. SRDS: What do you think readers can gain by reading stories with art tie-ins? MFB: Hopefully a greater appreciation for and curiosity about art and its beauty and value; also, I hope it might stir a desire in readers to find out more about the time period that helped bring the art into existence. SRDS: Are you working on a new historical novel with an art and artist(s) thread? If so, will you please share with us a bit about the upcoming book. MFB: I have just started on the first of a series of historical mysteries starring—who else? John Singer Sargent and Violet Paget! I had learned so much about them for my Portraits novel, and their voices and characters were so vivid to me, that I found they wouldn’t leave me alone! Violet in particular has a presence in my head that compelled me to write the new series with her as first-person narrator, looking back from later years to now tell the stories of her and John’s youth. They were best friends from the age of ten or so, born the same year, and as I start the series when they’re both twenty-one years old, I think it’s going to be thrilling to follow them through their respective creative careers – Violet as a prolific writer and literary/social critic, and John of course as the most celebrated portrait painter of his time. The series begins in 1877, the Victorian Era, and will carry on through WWI, so I’m very happy to contemplate writing book after book for many years to come! The first book will be called The Spoils of Avalon, and it has alternating chapters set in 1877 (with Sargent and Paget) and in 1539 (mainly in Glastonbury, during the final Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII). Of course the two story lines are related, and it all comes together quite wonderfully at the end (if I do say so myself!). SRDS: Any further thoughts on art in fiction you’d like to share or expand on?

MFB: One of the quotations I use at the beginning of my novel is from Oscar Wilde, who was an acquaintance of Sargent’s, where he said, “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not the sitter.” I tried first to get myself inside of Sargent’s time, behavior, thoughts and feelings, and then by studying his portraits, draw out a deep sense of both what he felt about the sitter and the painting, as well as what he saw in his subject that interested him. The enigmatic “Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” was the catalyst for my book, when I first saw that painting (in person) in 1999. There is something so very mysterious and dark about the painting, which can scarcely be said to be a portrait in the conventional sense. It’s very large, too, a perfect 7 x 7 foot square. Of course, it’s easy to say that Sargent was young and ambitious, wanting very much to make a splash at the annual Salon with a strange and large painting (which he often did), but I felt so strongly that there was something more here, that I just had to delve into it to find some way to explain it. That’s why I love historical fiction SO much – because we’re all human, we have access to the same human feelings, motivations, darkness and joys that all humans through time have felt – and fiction writers in particular get to play with all the sources and effects through time: paintings, sculptures, books, events, costumes, food, habits – and then exert their imagination and all their experience to bring home the eternal truths of the human spirit in a very accessible way to the modern reader. Hooray for historical fiction!  About the author: Mary F. Burns is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society and was a member of the HNS Conference 2013 board of directors. Her debut historical novel J-The Woman Who Wrote the Bible was published in July 2010 by O-Books (John Hunt Publishers, UK), and her second book, Portraits of an Artist: A Novel about John Singer Sargent, was published in 2013 by The Sand Hill Review Press (Menlo Park, CA). She has also written two cozy-village mysteries in a series titled The West Portal Mysteries. Ms. Burns was born in Chicago, Illinois, grew up in the western suburb of LaGrange, and attended Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, where she earned both a Bachelor and a Master’s degree in English, along with a high school teaching certificate. She relocated to San Francisco in 1976 where she now lives with her husband Stuart in the West Portal neighborhood. Ms. Burns also has a law degree from Golden Gate University.

About the author: Mary F. Burns is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society and was a member of the HNS Conference 2013 board of directors. Her debut historical novel J-The Woman Who Wrote the Bible was published in July 2010 by O-Books (John Hunt Publishers, UK), and her second book, Portraits of an Artist: A Novel about John Singer Sargent, was published in 2013 by The Sand Hill Review Press (Menlo Park, CA). She has also written two cozy-village mysteries in a series titled The West Portal Mysteries. Ms. Burns was born in Chicago, Illinois, grew up in the western suburb of LaGrange, and attended Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, where she earned both a Bachelor and a Master’s degree in English, along with a high school teaching certificate. She relocated to San Francisco in 1976 where she now lives with her husband Stuart in the West Portal neighborhood. Ms. Burns also has a law degree from Golden Gate University.

For more information about Mary’s work: www.maryfburns.com www.portraitsofanartist.blogspot.com and www.jthewomanwhowrotethebible.com

Join us next Saturday June 14th for an interview with Michael Dean,

author of I,Hogarth

Interview posting schedule: May 31st Susan Vreeland, June 7th Mary F. Burns, June 14th Michael Dean, June 21st Donna Morin Russo, June 28th Alana White, July 5th Maryanne O’Hara, July 12th Stephanie Cowell, July 19th Cathy Marie Buchanan, July 26th Alicia Foster

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing & yoga workshops. She writes features for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first art-related historical novel, CUT FROM THE EARTH. A story of Portuguese tile and its surprising makers – The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 — and the wisdom of nature to guide and heal. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com & Join Facebook group “Love of Art in Fiction“

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing & yoga workshops. She writes features for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first art-related historical novel, CUT FROM THE EARTH. A story of Portuguese tile and its surprising makers – The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 — and the wisdom of nature to guide and heal. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com & Join Facebook group “Love of Art in Fiction“